Chapter 3. Collective Bargaining and Collective Agreements

- 5. Case Studies

-

[Case Study 2]

A Case of Recovery of Infringed Managerial Rights through Collective Bargaining

1. Outline of Major Events

A labor union of civil employees employed by a certain autonomous local government (hereinafter referred to as “the employer”) was established ten years ago, and had obtained rights for its members by getting involved in managerial rights issues and expanded paid union time through collective agreements. The employer could not operate its workforce efficiently due to the labor union’s involvement in managerial rights issues, and had also been gradually handicapped in its work performance, due to an excessive amount of paid union time. The existing collective agreement expired in April 2008, and under the above-mentioned circumstances, the labor union and the employer had been unable to renew the collective agreement despite repeated attempts at collective bargaining in ten meetings. The employer, therefore, commissioned me with negotiating authority in March 2009, asking me to remove the union’s infringement of the employer’s managerial rights, and reduce the labor union’s excessive amount of paid union time. As a labor attorney, I implemented 24 collective bargaining meetings with the labor union between March and October 2009. Due to the sincerity of the negotiations, the employer has recovered the infringed managerial rights in the new collective agreement, and the number of hours of paid union time has been cut in half. Of course, in return for this, the employer improved working conditions: extending retirement age, increasing the health checkup subsidy, introducing interim severance pay, etc. Finally, we concluded negotiations with a collective agreement, which included mutual gain.

2. Collective Bargaining Summary

1) The employer gave a draft proposal of a collective agreement to the labor union (Feb. 17, 2009)

2) 1st & 2nd collective bargaining sessions on March 11th and March 19th

- The labor union did not recognize the company’s labor attorney as the employer’s negotiating representative.

3) 3rd ~ 7th collective bargaining sessions on April 1st, April 15th, April 24th, and April 29th

- The labor union did not respond to the employer’s proposed collective agreement draft, but instead requested collective bargaining on wages first.

4) 8th collective bargaining session on May 6th

- The labor union unilaterally declared an industrial dispute, held a press conference and announced a strike against the employer on the morning of May 13th.

5) The employer informed the labor union of the cancellation of the collective agreement on the afternoon of May 13, 2009, effective 6 months later on November 13th.

6) The labor union applied for mediation of the industrial dispute from the Labor Relations Commission, but both sides rejected the mediators’ draft proposal (May 20th~29th)

7) After negotiations broke down, the labor union held more than 50 demonstrations in front of City Hall from May to October.

8) The labor union requested a meeting with the mayor and met with the relevant director on June 10th.

- Both parties agreed to resume practical collective bargaining.

9) 9th collective bargaining session on June 17th

The union held a sit-in strike demanding at least three collective bargaining meetings a week.

10) 10th collective bargaining on June 24th

- Both parties agreed on one collective bargaining session per week, and the labor union began responding to the employer’s initial draft.

11) 11th ~ 21st collective bargaining sessions (June 1st ~ September 24th)

- The union agreed to most articles in the employer’s draft, excluding certain controversial issues regarding managerial rights, disciplinary action, full-time union officials, etc.

12) 22nd & 23rd collective bargaining sessions on September 30th and October 14th

- The labor union compromised greatly by proposing a collective agreement very similar to the employer’s original draft agreement.

13) Both parties agreed on the new collective agreement and held a signing ceremony on October 30th, 2009.

3. Background to the Employer’s Cancellation of the Collective Agreement

1) The labor union’s perspective

(1) The original collective agreement had a provision where the collective agreement would continue to be effective even upon expiration, as long as negotiations were taking place. Another provision allowed for automatic renewal of the collective agreement, as long as neither party requested a revision of the current collective agreement. Therefore, due to these provisions, the labor union felt it did not have to respond to the employer’s proposed collective agreement, which it felt was significantly disadvantageous compared to the existing collective agreement.

(2) The labor union was unwilling to give up the original collective agreement because it represented the rights they had acquired during their 10 year struggle against the employer.

2) The employer’s perspective

(1) The original collective agreement was effective for two years and when that period expired, it was no longer valid.

(2) The employer explained that it is not seeking to unfavorably revise current working conditions, but to recover its infringed-upon managerial rights, which are fundamental rights of the employer.

(3) Although the employer had held negotiations with the labor union 8 times, the labor union did not respond to the employer’s draft at all, so the employer decided to cancel the collective agreement in order to start practical neg

otiations on the proposal.

4. Details of Recovered Managerial Rights

1) Revision of provisions requiring consultation with, and agreement from the labor union

(1) Establishment or revision of regulations

- Previous: When the employer intended to establish, revise or abolish regulations and rules related to labor union members, including the rules of employment, the employer had to consult the labor union in advance.

- Revised: This provision has been replaced with Article 94 (Procedures for Preparation of and Amendment to Rules of Employment) of the Labor Standards Act.

(2) Restriction on hiring irregular employees (like daily workers)

- Previous: When the employer intended to hire irregular employees, the employer had to consult the labor union in advance concerning the necessity for employment, employment period, number of workers, and positions.

- Revised: In principle, the employer shall not use irregular employees (like daily workers) on jobs that labor union members are engaged in.

(3) Introduction of new technology

- Previous: The employer had to provide all information related to new technology to the labor union and could introduce it only after consultation with the labor union.

- Revised: When the employer intends to introduce new technology or change current technology, the employer shall provide relevant information in advance to the labor union.

(4) Outsourcing or subcontracting

- Previous: The employer shall determine whether outsourcing or subcontracting is necessary through advance negotiations with the labor union.

- Revised: When there is a change in employment relations or working conditions, the employer shall listen to the opinions of the labor union.

2) Revision of disciplinary provisions

(1) Severity of disciplinary punishment

- Previous: The types of disciplinary punishment were based upon the number of times an employee behaved inappropriately. (For example, disciplinary dismissal was only possible if a person used violence against his/her superior three times.)

→ This means that the employer could not dismiss a violent union employee until he/she was violent toward his/her superior three times. This article infringed on the employer’s rights to bring about justifiable disciplinary action.

- Revised: The type of disciplinary punishment is determined by the severity of the violation and the degree of negligence. The previous provision, ‘number of times an employee behaves inappropriately’ was deleted.

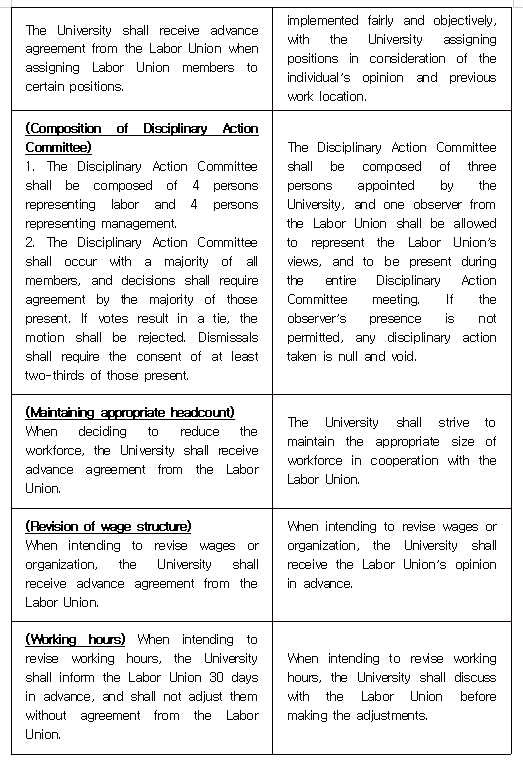

(2) Composition of the disciplinary action committee

- Previous: The disciplinary action committee consisted of five members: three managers representing the employer and two representatives for the union members. Decisions were made by an affirmative vote of a majority of the members present at a meeting where a majority of all members are present.

→ As it was very difficult to get all the required people for a disciplinary action committee to discipline a union member who violated the rules, the employer often could not put together a disciplinary action committee when it was necessary. I persuaded the labor union that what they really wanted was a fair disciplinary process, not to interfere with that process taking place.

- Revised: The disciplinary action committee shall be composed of three persons designated by the employer, who shall provide an observer the opportunity to state his/her opinion, and will guarantee his/her presence at the disciplinary committee meeting until the final decision-making time. If the observer’s presence is not allowed, any disciplinary decisions are null and void.

3) Revision of other unreasonable provisions

(1) Reduction of the number of full-time union officials and paid union time

- Previous: Two full-time union officials (for 230 union members) were permitted, and 4 hours per day (88 hours per month) were allowed as paid union time for branch representatives of the labor union.

- Revised: The number of full-time union officials was reduced to one, and paid union time for branch representatives was reduced to 8 hours per week.

(2) Deletion of detailed provisions related to the Labor-Management Council

- Previous: There were separate provisions for the Labor-Management Council in the collective agreement: [Labor-Management Council], [Matters to be Reported], [Matters Subject to Consultation], [Matters Subject to Council Resolution], [Provision of Business Data], and [Effect of Matters Subject to Council Resolution]

→ As the detailed provisions of the Labor-Management Council are stipulated in the collective bargaining agreement, the labor union can request collective bargaining every quarter and the company had to provide it.

- Revised: all provisions of the Labor-Management Council, except one, [Composition and Operation of the Labor-Management Council], have been deleted from the collective agreement.

(3) Obligation to respond to collective bargaining requests

- Previous: ‘When one party requests collective bargaining, the other party shall respond to that demand.’

→ Both parties have a duty to keep the peace during the effective period stipulated in the collective agreement, but the “Obligation to respond to collective bargaining requests” can nullify this duty.

- Revised: Added ‘demands for collective bargaining can only be made within three months of the collective agreement expiry date.’

5. Background to the Union’s Compromise and Evaluation of the Collective Bargaining Process

1) Background to the labor union’s compromise

(1) The employer’s consistency in explaining the purpose behind its desire for a new collective agreement

The employer consistently explained that the desire for a new collective agreement was not to worsen existing working conditions, but to recover managerial rights that were being infringed upon in the existing collective agreement. The labor union gradually tried to find a compromise, because otherwise it would lose all acquired contractual rights once the collective agreement expired. Under the circumstances, the labor union faced significant loss if it allowed the collective agreement to expire, so it accepted most provisions of the employer’s proposed collective agreement just before termination of the previous collective agreement.

(2) The employer’s consistency in exhibiting reliability during collective bargaining

During the weekly negotiations, the employer consistently exhibited good faith and sincerity, rotating the meeting places of both parties. Also, the umbrella labor union did not significantly interfere with the negotiations thanks to a long time confidence that had developed between the labor union and the employer.

(3) The labor union’s inability to effect changes with protests

After mediation of the industrial dispute broke down, the labor union staged more than 50 protests in front of City Hall, but the employer consistently refused to respond to their demands, so the labor union’s collective actions did not bring about their expected result.

2) Evaluation of the collective bargaining process

This collective bargaining agreement was remarkable in that it marks a break from the existing practice of an employer unilaterally giving in to a labor union’s demands. The employer was able to recover managerial rights infringed upon by the previous collective agreement, by negotiating sincerely with the labor union, and the labor union was also able to acquire practical gains. Therefore, these negotiations have helped both parties to avoid the existing pattern of confrontation and combative working relations, and instead build up a mutually complementary and cooperative relationship.

[Case Study 3]

Evaluation of a Collective Bargaining Agreement between a Janitors’ Labor Union and the University Employer

1. Introduction (Summary)

On May 27, 2014, a signing ceremony was held for a collective bargaining agreement between a certain university (hereinafter referred to as “the University”) and the University janitors’ labor union (hereinafter referred to as “the Labor Union”). As representatives of both the Labor Union and the University management signed the collective agreement, it marked an end to the labor disputes that had continued for more than a year and established a new employment relationship. In this article, I would like to review the content of the collective agreement, and the reasons why it took such a long time, in the anticipation of some lessons against making the same mistakes in the next collective bargaining sessions.

In July 2013 when the University had difficulty negotiating with the newly established Labor Union, it gave this labor attorney authority to negotiate on its behalf. The University janitorial staff were employed as regular employees from an outsourcing company on March 1, 2013. The University and the Labor Union began collective bargaining at the time, but this devolved into labor disputes that involved the Labor Commission until May 2013. The University explained to this labor attorney that since there were no items the two parties could agree on, I could start the collective bargaining from the beginning. After drafting and obtaining University approval for a counter-proposal to the Labor Union’s collective agreement proposal (80 articles), I was ready for collective bargaining.

The two parties’ negotiating teams began their bargaining sessions on July 16, 2013. The Labor Union’s negotiating team was composed of seven persons: two union officers from the umbrella union (the Seoul and Gyeonggi branch of the Korean Public & Social Services and Translation Workers’ Union), three union officers from the janitor’s union, and two observers from the building management team (outsourced workers at that time). The University negotiating team consisted of three persons: this labor attorney as the chief negotiator, a team leader in charge of general affairs, and the staff member responsible for managing the cleaning services on campus. During the first negotiating session, when the University team submitted the counter-proposal to the Labor Union, the Labor Union showed in the collective bargaining minutes that the previous University bargaining representative had already agreed to 50 of the 80 items. The previous University representative who was in charge of cleaning services explained that he had just signed the meeting minutes without approval from his superiors as the Labor Union had assured him that the meeting minutes could change at a later time. This labor attorney then told the Labor Union that the meeting minutes that the previous University representative had signed were of agreements that the University could never accept, and any agreements made were mistakes by the staff member who had signed the minutes. I then requested that the meeting minutes be officially determined as void.

For this action, the Labor Union filed a complaint with the Labor Office against the University president, the general manager, a team leader in charge of general affairs, and the new chief negotiator (this labor attorney) for unfair labor practice in early August 2013. The Labor Union took several actions in protest including a press conference, a one-person picket of City Hall, a regular Wednesday sit-in protest at the University headquarters, and a slowdown of cleaning services. The chief Union negotiator took to tearing up the University’s counter-proposal at the bargaining table, and throwing his hot coffee at the team leader in charge of general affairs for being late to one of the collective bargaining sessions.

In November, after investigation, the Labor Office found there to be no evidence of unfair labor practice by the University declaring the two meeting minutes void, and threw out the Labor Union’s complaint. After this, the Labor Union demanded that there be no discrimination between the university labor unions, and that the University should allow this Labor Union’s activities as it allowed other unions their activities. The University accepted some of the Labor Union’s demands, and both parties managed to reach agreement on 20 items, including union activities.

In February 2014, major disputes moved on to job security, protection of union activities, and allowance of paid time off for one full-time union officer. In terms of job security, the Labor Union demanded extension of the retirement age to 70 (instead of the current 65 years of age), in light of over 20 union members expecting to have to retire at the end of the year if this was not done. When the University rejected this demand, the Labor Union began taking action on February 29, 2014, hanging up approximately 30 banners around the campus, and setting up a tent at a building near the main gate to engage in a sit-in strike.

By April 1, 2014, the number of union members had dropped to just half of the total janitorial staff. In this worsening situation, the Labor Union had to withdraw its demand for extension of the retirement age to 70, and instead accepted that the University would work to protect job security. As the Labor Union could not perform union activities for a long time without a collective agreement, it seems to have decided that the next best alternative was to accept realistic measures. The Labor Union then suggested to the University that a working level negotiating team be formed to draw up a collective agreement as soon as possible, which the University accepted. This working-level team consisted of three members from the Labor Union and three University representatives. The working level negotiating teams reached agreement on all remaining items and finalized the collective agreement.

2. Rejection of Meeting Minutes & Unfair Labor Practice

When a labor union was established for the janitorial workers and demanded a collective agreement, the University appointed the staff member in charge of cleaning services as its collective bargaining representative. This particular staff member had no experience negotiating with labor unions before, and as the Labor Union repeatedly asked him to sign the meeting minutes, he did so simply to confirm that he had negotiated with the Labor Union. When this labor attorney, in preparation for collective bargaining, reviewed the contents of the signed meeting minutes, there were many articles that the University must not accept in any situation.

Some examples: “Anyone engaging in unfair labor practice as defined in Article 81 of the Trade Union Act shall be subject to disciplinary action.” “The Disciplinary Action Committee shall consist of 4 representatives from the Labor Union and 4 from the University. Half or more of the Disciplinary Action Committee shall be present, and consent from a majority of those present is required before disciplinary action can be taken.” The University also disagreed with such requirements as it needing approval from the Labor Union when handling many different personnel issues.

For these reasons, the University could not accept the meeting minutes. In addition to filing a complaint against all negotiating team members of the University including the University president for unfair labor practice, the Labor Union also demanded the replacement of this labor attorney as University negotiating team representative.

The Labor Union delayed collective bargaining until the Labor Office determined there was insufficient evidence of unfair labor practice by the University, and dismissed the case on November 27, 2013.

3. Issue Related to Extension of Retirement Age

When the janitorial workers were employed by the outsourcing company, there were no regulations regarding retirement age, but upon direct hiring by the University in March 2013, the University’s retirement age regulations became applicable. Their wages also increased considerably because they received the service fees normally paid to the outsourcing company, and other working conditions like welfare benefits improved as well. However, as the retirement age had recently been set at 65 (although the University allowed application for two years’ delay in mandatory retirement), 22 of the approximately 60 janitorial staff were due to retire at the end of 2014 in accordance with retirement regulations. The Labor Union demanded extension of the retirement age to 70, but as the University received a subsidy for janitors’ wages from the Seoul Metropolitan Government, this was impossible without the city government changing its policy. The Labor Union had to accept the fact that the University could not agree to any extension of the retirement age without the consent of the city government, and on April 1, 2014, withdrew this demand, accepting that the University would seek to provide job security.

4. Articles Related to Personnel & Managerial Rights

Articles related to personnel and managerial rights refer to an employer’s authority to make decisions affecting personnel, such as determining regulations on working hours, workplace, work assignments, and disciplinary action, etc. It would be an infringement of its personnel and managerial rights if a company were to be required through inclusion in the collective agreement such conditions as needing prior agreement from or advance consultation with the labor union, or having to seek the labor union’s opinion before making such decisions. When the Labor Union in question requested collective bargaining, many of the articles they presented infringed on these employer rights. However, at the end of the day, many of these demands were moderated.

5. Conclusion (Evaluation of the Collective Bargaining Process)

Generally, collective bargaining with new labor unions results in many disputes, and the situation in this article was no exception. When beginning these particular collective bargaining sessions, I followed two principles: 1) the collective agreement shall not infringe on the employer’s personnel and managerial rights; and 2) the collective agreement shall create an employment situation that is sustainable for the University later.

There were three major issues in the course of the collective bargaining. The first issue was that by signing the meeting minutes, the former University representative agreed on 50 of the proposed items from the Labor Union before this Labor Attorney came to represent the University as chief negotiator. This mistake by the previous representative resulted in extended conflict between labor and management when the original meeting minutes were rejected: the Labor Union filed a complaint against the responsible University managers for unfair labor practice, which also served to delay the collective bargaining process as both sides had to wait for a decision from the Labor Office. The second issue was the Labor Union demanding extension of the retirement age from 65 to 70. When this was refused, the Labor Union hung about 30 protest banners around the campus and staged a sit-in protest in a tent at one of the gates. Since any changes to the retirement age required city government approval, the University could not agree to this demand, even though it was understood that this demand arose from the fact that 20 of the 60 employees were supposed to retire by the end of 2014. The third issue was the infringement of the employer’s personnel and managerial rights, which was the strategy the Labor Union used to protect jobs. In practice, when an employer allows such rights to be restricted in the collective agreement, labor disputes increase and rifts in labor-management relations arise.

Although a reasonable collective agreement between the University and the Labor Union was ultimately concluded, one major problem was the length of time it took: 15 months. There were two reasons for this. Firstly, the Labor Union involved the umbrella union at the bargaining table, resulting in the first draft proposal containing many items that infringed on the employer’s personnel and managerial rights, and demands for working conditions and union activities beyond what the University could afford to accept. Secondly, the University had no specialized staff with the knowledge of labor law necessary for dealing with a labor union. As the Labor Union received professional support from its umbrella union, the University decided to hire an outside labor specialist for the professional legal support they lacked. Due to a failure to cooperate and compromise, the Labor Union and the University were unable to conclude a collective agreement except after labor disputes and a significant amount of time and effort.

Despite the aforementioned problems, the final collective agreement was accepted by both parties. The Labor Union was recognized as a labor union, receiving an office and workers’ lounges, paid time-off for union activities, and additional off-days, etc. For its part, the University also views the outcome as a success, as it was able to protect its personnel and managerial rights as an employer, and sign a sustainable collective agreement. It is desirable that the resulting agreement, concluded after much struggle, will play a pivotal role in maintaining peace between labor and management, and allow both parties to base their labor relations on mutual benefit.

[Case Study 4]

Forced Business Closure as a Result of a Labor Union’s Abuse of its Rights

1. Summary

This case is about a taxi company in Yeosu, South Jeolla Province, that actually had to shut down its business due to abuses by the labor union of its own rights. These same abuses resulted in the new employer, who had purchased the taxi company, also having to shut down. The taxi company had been unable to increase the deposit money which taxi drivers have to turn over to the company out of their daily earnings (hereby referred to as the “daily deposit”) for its last ten years, which resulted in accumulated deficits over a long period of time. Furthermore, the company was not allowed to discipline any employees who violated company regulations over the same period either.

This company was the biggest taxi company in Yeosu about 10 years ago, with 80 taxis. The company and the labor union agreed on a daily deposit amount in their collective agreement in 1998. The daily deposit stipulated in the collective agreement was much lower than that of any of the other taxi companies, and so this helped to maintain peace between management and labor for some years. However, from 2000, the company started facing difficulty from operational deficits due to rising prices and fuel costs, etc., and requested an increase in the daily deposit, but the labor union refused, arguing that the company’s explanation of the reasons for the monthly deficit could have been falsified. The employer then completely laid out the company’s financial situation to the labor union in the hopes of being able to rescue the company, and desperately demanded the drivers’ daily deposit be increased up to the minimum break-even point. However, this was impossible, as the labor union was unwilling to compromise. In the end, the employer had to sell the business in February of 2006, due to its accumulated debt.

A new employer purchased the taxi company with a verbal promise from the labor union that it would increase the daily deposit, but when the new employer purchased the company, the labor union allowed the increased daily deposit for only two months, after which the labor union returned to the previous daily deposit. When the new employer decided to stop subsidizing fuel in order to prevent another deficit, the union members submitted their daily deposit after deducting an amount equivalent to the fuel subsidy. The company, following the disciplinary procedures in company regulations, then dismissed several union officers who had led other union members to deduct the fuel subsidy from their daily deposit. However, the Labor Relations Commission ruled that the dismissals were unfair in that the company did not observe the expired collective agreement’s disciplinary process, which was that “the disciplinary action committee shall consist of an equal number of representatives from the company and the labor union, and its decisions shall be decided by a two-thirds majority of the committee members present.” The new employer could not raise the taxi drivers’ daily deposit amount, and was also told that the Labor Office had decided that the company’s cessation of a fuel subsidy was illegal. Again, in the end, the new employer had to give up the business, due to the accumulated debt, only two years after purchasing the company.

2. Timeline of Major Events

1. 1979 : The taxi company was established.

2. May 1, 1998 : The drivers’ daily deposit, 65,000 won, was stipulated in the collective agreement.

3. July 2004 : A deficit of 10 million won per month started occurring, due to the rise in fuel costs. The company demanded that the labor union accept a 5,000 won increase om the drivers’ daily deposit, the minimum to break even, but the labor union refused.

4. Oct 29, 2004 : The company notified the labor union of the cancellation of the existing collective agreement.

5. Apr ~ May 2005 : The labor union went on strike for two months to prevent the sale of the taxi company.

6. Dec 2005~Feb 2006 : The taxi company suspended business for three months due to accumulated debt, and then was sold.

7. Mar ~ Apr 2006 : A new employer purchased the company after obtaining a verbal promise from the labor union that they would raise the drivers’ daily deposit by 9,000 won. However, the labor union returned to the previous daily deposit two months later.

8. May 2006 : After two months, when the new employer continued to deduct the increased daily deposit, the employees sued the company for these deductions, and the Labor Office ordered the company to return these deductions to the employees.

9. May ~ Nov 2006 : The new employer demanded that the labor union raise the drivers’ daily deposit so the company could stop running a deficit. Negotiations with the labor union were held over more than twenty sessions, but the labor union rejected the increase to the end.

10. After Nov 2006 : After sufficiently explaining the need to stop the fuel subsidy, the company stopped subsidizing fuel costs. The union members then reduced their daily deposit to 47,000 won, after deducting 18,000 won, equivalent to the fuel subsidy.

11. Nov 2006 : The company dismissed key union officers who defied the company’s decision to cease the fuel subsidy.

12. Dec 19, 2006 : The Labor Relations Commission ruled that the dismissals were unfair because the company violated disciplinary procedures.

13. May 21, 2007 : The employer appealed, but lost the case.

14. Aug 27, 2008 : The new employer gave up the business due to the debt load.

3. Necessity of Increasing the Daily Deposit and Labor Union Objections

(1) Necessity of increasing the taxi drivers’ daily deposit

When the company and the labor union determined the drivers’ daily deposit of 65,000 won in the collective agreement in May 1998, fuel cost 222 won per liter, but by June 2006, it had risen to 737 won: a 330% increase. During this period, the base taxi fare was 1,300 won, and increased to 1,800 won. However, the taxi drivers’ daily deduction did not increase due to the labor union’s continuous objections.

(2) A written statement from one of the former company presidents

My company had the best working conditions of all taxi companies in July 2004. Their average monthly income was 300,000 won more than their counterparts at other taxi companies, and thanks to this situation, we were awarded a prize by the Minister of Construction and Transportation in the field of labor-management relations. However, with the rise in fuel costs, the company could not share any profit with its stockholders, and even the company’s invested capital was at risk, due to the accumulated debt. The company had been losing, on average, 10 million won every month.

At the emergency board meeting, I was elected the new representative director. Based on my three basic standards of company management like the principle of trust, mutual benefit, and transparency, I started to negotiate with the labor union and laid out the company’s financial situation for the labor union to see (the union inspected the company’s business practices three times), but the labor union would not agree to an increase of their daily deposit. The company requested only 5,000 won more, the minimum to break even, explaining that the company would do business without profit for the time being so as to rescue the company, but the labor union refused, repeatedly claiming the company was not losing money. The board meeting concluded with the company still unable to recover from its accumulated fuel and other debts, and in the end, was sold, with the entire amount from sale going to payment of company debts.

A considerable number of reasonable union members suggested the daily deposit be increased an additional 10,000 won (even in this case, an employee could receive, on average, 100,000 won more per month than at other companies) demanding that the company suspend its sale, but their efforts availed nothing, due to threats and interference from a few militant union members.

(3) Comparison of wages versus taxi drivers’ daily deposit

– prepared by a certified public accountant (as of Nov 1, 2006)

1) Company income per driver (daily deposit): 65,000 won x 25 days = 1,625,000 won/month

2) Labor costs(direct costs + indirect costs)→ 1,976,609 won per driver per month

- Direct labor costs: basic pay, long-term service allowance, car wash allowance, summer vacation allowance, tuition subsidy, severance pay reserve, insurance premiums for the four social security insurances, compensation for unused annual/monthly leave, paid leave allowance (5 days), gift expenses, fuel subsidy (26.7 liters) → 1,272,645 won

- Indirect labor costs: management staff labor costs, general expenses, car insurance, depreciation of car values, car repairs, dividends to stockholders → 703,963 won

3) Company income versus individual labor costs

1,625,000 won (company income) – 1,976,609 won (labor costs)

= -351,609 won (deficit per individual per month)

4. Loss of the company’s right to implement disciplinary action

Through negotiation with the labor union, the company introduced a disciplinary process in the collective agreement which stipulated, “the disciplinary action committee shall consist of an equal number of representatives from the company and the labor union, and decisions shall be made by a two-thirds majority of the committee members present.” The company gave up its right to unilaterally take disciplinary action in order to include the labor union as a business partner and to cooperate in a mutually beneficial way. Unfortunately, the company was not able to take disciplinary action against even one union member over the company’s last ten years on account of the requirements within the disciplinary process. Consequently, sometimes union members cursed the employer and neglected to carry out their duties properly. Union members also frequently caused car accidents. As a result of the lack of disciplinary action, the company had to pay more in annual car insurance premiums than other companies: more than 2 million won per taxi, compared to about 1 million won per taxi for the company’s competitors. This was as a direct result of the company’s inability to maintain ethical standards through disciplinary action. What is worse, under this disciplinary process, the company couldn’t even punish an employee who sued the employer without justifiable reason. This resulted in a collapse of order within the company, so manager directions were not adequately implemented.

5. Related judicial rulings and administrative interpretation

If a collective agreement expires, provisions concerning disciplinary process continue to be effective as normative sections. Jan 25, 2007, Labor Relations-293

Although the effective period of the collective agreement expires or the collective agreement is declared invalid by one party cancelling the agreement during the autonomous extension period, ‘standards concerning working conditions and other matters concerning the treatment of employees’ (namely, the normative section), as prescribed in the collective agreement, would remain in effect as the working conditions of individual employees. If the employer wishes to revise the normative section, he shall conclude a new collective agreement in accordance with legitimate procedures, or revise the rules of employment and obtain collective consent of the employees concerned. Supreme Court Ruling, Jun 9, 2000, 98da13747

In cases where the employer agrees with the labor union in the collective agreement that “when taking disciplinary action, the disciplinary action committee shall consist of an equal number of representatives from the company and the labor union, and its decision shall be decided by a two-thirds majority of committee members present,” it is true that it is practically impossible to discipline employees who violate company regulations. Although this makes it difficult to take disciplinary action, the validity of the disciplinary process as stipulated in the collective agreement, will still hold.

6. Conclusion

In this labor case, as in other cases where the employer gives up a certain range of personnel and management rights in order to maintain peace with the labor union, the results are evident. The loss of managerial and personnel rights will lead to failure of the business, reducing competitiveness in the market and employee job security as well. Therefore, when an employer establishes autonomous agreement by collectively bargaining with the labor union, the employer should not forget that he or she should negotiate with the labor union within certain boundaries: fundamental employers’ rights, namely, personnel and managerial rights, should not be given up in the collective agreement. If the employer hands over personnel and managerial rights to the labor union, it should be remembered that negative consequences will occur for the employer and the labor union in the long run.