Chapter 4. Industrial Disputes and Industrial Actions

- 1. Industrial Disputes and Industrial Actions

-

1. Industrial Disputes

The term “industrial disputes” refers to any controversy or difference arising from disagreements between a labor union and an employer or employers' association concerning the conditions of employment such as wages, working hours, welfare, dismissal, and other issues. Article2, subparagraph5, of Labor Union Act

(1) Disputes arising from disagreements

Disagreements between the two parties are not always considered industrial disputes. However, if the two parties engage in collective bargaining but fail to reach an agreement, then their conflict is considered an industrial dispute.

(2) State of disputes

Industrial disputes signify a state of disputes. Accordingly, it is a different concept from an industrial action under Article 2, subparagraph 6, of the Trade Union Act, which is an actual practice of collective power. However, in actual practice it is difficult to differentiate between the occurrence of industrial disputes and the occurrence of industrial actions. In general, industrial actions are taken for a certain period of time after the parties of the Trade Union Act apply for mediation of an industrial dispute.

2. Industrial Actions

Industrial actions refer to struggles between the labor union and the employer to take advantage of the state of labor disputes in order to accomplish their goals. This shall not only contain “any controversy or difference arising from disagreements between a labor union and an employer with respect to the determination of conditions of employment”, but also include “actions which obstruct the normal operation of a business.”

Accordingly, industrial actions are such actions as strikes, slowdown strikes, lockouts, and other activities to obstruct the normal operation of a business, but those actions such as assembling outside working hours or wearing ribbons are not industrial actions.

Industrial actions engaged in by employees can employ typical methods such as strikes, slowdowns and production management strikes, and by subsidiary methods such as picketing, plant occupation, and boycotts. Sometimes, work-to-rule can be utilized.

(1) Strike

A strike is an industrial action where the workers collectively refuse to provide labor or to stop production and bring financial loss or loss of business to the employer.

The employees' collective refusal to work during working hours, unless it is deemed as illegal for another reason, may simply be a failure to comply with the obligation to provide work. However, if such refusal to work prevents the regular functioning of the business but is not a legitimate industrial action, it may constitute a criminal offense of business obstruction. Supreme Court ruling on Apr, 23, 1991, 90Do2771.

(2) Slowdown strike

In a slowdown strike, employees provide labor with deliberate inefficiency.

(3) Production management

Under production management, the employees unite to defy the employer's orders and occupy the plant and operate the business as they wish.

(4) Boycott

In a boycott, the labor union deters the purchase of their employer's or contractors' products through appeal or advertisement, or collectively avoids using the facilities provided by the employer.

Boycott itself as one type of industrial action is justifiable, but when the labor union spreads untruths to promote boycotts, such behavior cannot be justified.

(5) Picketing

Picketing is one industrial action by which the labor union persuades union members who are not willing to attend strikes and, instead, try to work, to cooperate with the strikers or to prevent them from holding anti-strike activities. Picketing is used as an alternative to striking. The union usually hangs a placard at the main entrance gate of the workplace, and its members protest around the entrance gate of the company and shout slogans.

As usual, a strike may be supplemented by picketing or a sit-in or stay-in at company premises to ensure or strengthen the effectiveness of work discontinuance. Picketing itself is a justifiable action, so long as strike participants do not verbally abuse or threaten to use physical violence. Supreme Court ruling on Jul. 14, 1992, 91Da43800.

(6) Occupation of the company premises

A labor union’s occupation of company premises as one method of active industrial action is justifiable only when it is a partial occupation and does not prevent the employer from entering or leaving. However, if the labor union occupies the company premises entirely and exclusively, preventing all but union members from entering, and causes stoppage or disturbance of the company’s operations, such behaviors can be seen as beyond justifiable limits. Supreme Court ruling on Jun. 11, 1991, 91Do383.

Some union members occupied the front door and aisle leading to the office of the company head at the main building of a plant. They also sang and chanted during lunch breaks and at nighttime, preventing outsiders from coming into the main building and obstructing the normal functioning of the plant. In this case, their occupation and sit-ins were regarded as industrial actions. Supreme Court ruling on Jan. 15, 1991, 90Nu6620.

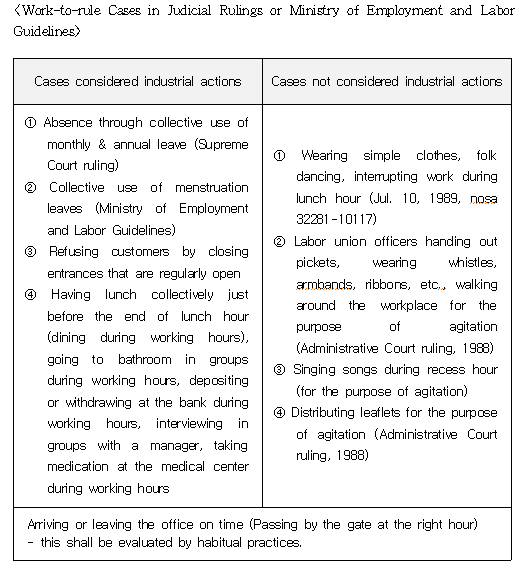

(7) Work-to-rule

Work-to-rule is used as a method to deteriorate the company's operational efficiency by observing very strictly the safety laws, which employees do not follow ordinarily, or by carrying out their rights in unusual ways.

The union, for the purpose of making a point, instructed union members (nurses) to use their monthly leave at the same time. This is an act of work-to-rule, which is a kind of industrial action. In addition, their working in plain clothes is also an industrial action, as they are required to wear uniforms for reasons of sanitation and a need to signify their position. Supreme Court ruling on Jun. 14, 1994, 93Da2916.

If employees, with the aim of having their demands met, refuse to do the holiday work that they usually did, such refusal is an industrial action as it undermines the regular functioning of the business. Supreme Court ruling on Dec. 26, 1997, 97Nu8427.

3. Employer Industrial Actions: Lockout

(1) Definition of lockout Article 46 of Labor Union Act

An employer may declare lockout to counteract an industrial action taken by the labor union. Lockout refers to "an employer's act of refusing to accept work provided by his/her employees" as a counteraction to the industrial action taken by the employees. It is a type of industrial action that an employer is allowed to take to guarantee an equal playing field in labor relations.

(2) Requirements for lockout

A lockout may not be done in a preemptive or offensive way. The lockout shall be carried out only after the union has taken industrial action. This means that a lockout declared before any industrial action by the union is unlawful. If a lockout is not withdrawn even after the union genuinely has declared a halt to the industrial action, the lockout shall be considered an offensive one and so shall be deemed unjustifiable. An employer who intends to lock out shall report in advance to the competent authority and the jurisdictional Labor Relations Commission.

(3) Effects of lockout

If a lockout is performed properly, the employer concerned is exempt from the obligation to pay wages for the lockout period.

(4) Ministry of Employment and Labor Guidelines and judicial rulings concerning lockout

1) Concept

A lockout is a situation in which the employer refuses to receive employees' service as a means to defy their industrial actions and prevent their entry. The lockout sustains the power balance between labor and management by allowing the employer to counteract industrial actions by the employees.

2) Requirements

① Opposing lockout

The employer usually implements an opposing or defensive lockout after inception of an industrial action. Therefore, the employer may only report a lockout after the labor union takes a legitimate industrial action following a cooling-down period (mediation period). MOEL Guidelines: Nosa 32281-1703, on June 24, 1998.

② Defensive lockout

A passive and defensive lockout is highly suggested if a counteraction is deemed unavoidable since aggressive and offensive lockouts are unjustifiable. In principle, the law prohibits a preemptive lockout or any measure taken that exceeds a considerable degree in scope and method of the industrial action. Daejeon District Court ruling on Feb. 9, 1995, 93Gahap566.

In one particular case, the union demanded a wage increase although the average wage at the company was higher than that of any other competitor company. The result was a breakdown of the wage bargaining process. The union resorted to work-to-rule as an industrial action, which was immediately followed by the employer locking them out. Given that the employer's lockout occurred only three days after the union's industrial action, the lockout cannot be justified. Supreme Court ruling on May 26, 2000, 98Da34331.

3) Methods

① Practical measures

A lockout is not legitimate if only the labor union is notified. Practical measures must be taken by refusing entrance of the employees to the workplace.

② Applicable to any industrial action

A lockout can be implemented during any industrial action, including slowdown strikes or work-to-rule actions.

③ Partial lockout and general lockout

Industrial actions are actions or counteractions, such as strikes, slowdown strikes, lockouts, and other measures taken by parties to labor relations to achieve their goals. As the labor union is allowed to initiate a general or partial strike, the employer may also choose to execute a general or partial lockout as a countermeasure. MOEL Guidelines: Hyupryeok 68140-327, on Aug.31,1998.

4) Effects

① Exempt from obligation to receive labor service and render wages

An employer has the right to refuse to receive labor service from his/her employees during a lockout. In addition, the employer is not obliged to render wages to employees who do not provide labor service due to a lockout, since wages mean remuneration for work. This exemption extends not only to union members subject to lockout but also to all other non-union employees. However, if an employee who is not subject to the lockout provides regular work for the company, contractual wages shall be paid for the service provided. MOEL Guidelines: Nosa 68107-338, on Nov.21,1994.

② Holidays and leave

As an employer can legitimately refuse to receive labor service from his/her employees subject to the lockout, the statutory holidays and leave according to the Labor Standards Act do not occur. MOEL Guidelines: Kungi 68040-1769, on Nov.10,1994.

③ Places off-limits to employees

i) Scope of off-limits

A lockout is a refusal to accept labor service in which the employer can prevent employees from entering the workplace by closing the company entrance gates or withdrawing employees from production facilities and precluding their labor service. Accordingly, employees who are noncompliant in leaving the workplace during a legitimate lockout may be subject to the criminal charge “noncompliance with a deportation order,” provided that a lockout is limited to production facilities or office facilities as it merely purports to prohibit employees from production and service. Nevertheless, the employer may allow union members entry to certain facilities necessary for union activities or welfare under rational scope, such as union offices, dormitory, canteen, and other facilities not related to production or work. MOEL Guidelines: Hyupryeok 68140-409, onOct.30,1998.

ii) Occupancy and lockout of the workplace

Despite legitimate occupancy of the workplace by employees before the lockout, the employer is given full ownership of the workplace and may request that the employees leave the working facilities during a lockout. Sustained occupancy at this time is illegal and offenders will be subject to the law for noncompliance with a deportation order. Supreme Court ruling on Aug.13, 1991, 91Do1324.

④ Available partial production

An employer does not have to stop production completely even during a lockout and may continue to receive service from employees not participating in strikes. MOEL Guidelines: Hyupryeok 68140-366, on Sept.9,1997.

⑤ Effects of illegal lockout

i) Employees' entry to workplace

If the employer's lockout is not legitimate, it is not a crime for the employees to enter the workplace where he/she has usually been permitted to enter, unless there is a special reason not to do so. Supreme Court ruling on Sep. 24, 2002, 2002Do2243.

ii) Wage payment during a lockout

In cases where a lockout serves as a measure against the union's industrial actions (strikes or slowdown strikes), the employer is exempt from the obligation to pay wages. However, in cases of preemptive and offensive lockouts, the wages must be rendered (shutdown allowance). MOEL Guidelines: KiJun 1455.9-11349, on Oct.30,1969.

5) Reporting

An employer shall, in advance, notify the Administrative Office and the Labor Relations Commission of his intent to begin a lockout. If a lockout is taken without prior notice, the employer may be subject to a fine up to 5 million won (Article 96 of the Trade Union Act). Here, the notice of intent to begin a lockout is not a substantial requirement but a procedural requirement out of administrative necessity. Therefore, failure to report a lockout does not necessarily affect the lockout’s legitimacy.

6) Cancellation

Industrial action by the union is the preliminary requirement of a lockout, as it is also the conditional requirement to sustain one. If the union decides to return to work, there remains no reason for continuing the lockout. However, if the union's decision to return to work does not seem genuine and there exists a likelihood of ensuing industrial action, the employer may justifiably prolong the lockout. MOEL Guidelines: Hyupryeok 68140-409, on Oct.30,1998.