Chpater 4. Remedy System of Dismissal

- 5. Comparison between the Labor Relations Commission

-

A foreign professor at a private university visited this Labor Law Firm for a consultation regarding his unfortunate employment case. This professor had had his employment contract renewed every(5) year for the past 5 years, but this had not been done the past February. The university stated that his employment contract had expired, as he was a fixed-term employee. The professor thought that his employment contract would be renewed according to the university regulations, as he had better-than-average scores in the teacher evaluation. He took legal action by submitting to the Labor Relations Commission an application for remedy for unfair dismissal, but his claim was rejected. He visited me to apply for an appeal.

Reviewing the details of his case, it was determined that, as he had been an assistant professor, he should have taken his original application for remedy to the Teachers’ Appeals Commission instead of the Labor Relations Commission. This individual could have been protected from the unfair rejection if he had known of the procedures of the Teachers’ Appeals Commission. This was a very unfortunate situation. Similar case: NLRC 99 Buno 165, Buhae 610, Jan 31, 2000. Railroad employees, to whom the Government Servant Act applies, submitted a claim of unfair dismissal to the Labor Relations Commission, rather than to the Appeals Commission. Due to this, the case was rejected.

In cases where an employee receives an unfair personnel disposition, he or she can find resolution by applying for remedy with the Labor Relations Commission. In 2015, the Labor Relations Commission handled 13,000 unfair dismissal cases, whereas in comparison, the Teachers’ Appeals Commission only disposed of 588, a relatively small number of cases, although the number is gradually increasing. Teachers’ Appeal Commission, “Collection of Decision Cases”, 2014.

Foreign professors, in particular, can be confused as to whether a claim should be made with the Teachers’ Appeals Commission, as they are fixed-term employees, but at the same time have the status of a teacher. The information below will enable the reader to understand the procedures of the Teachers’ Appeal Commission as they compare to the procedures for remedy with the Labor Relations Commission.

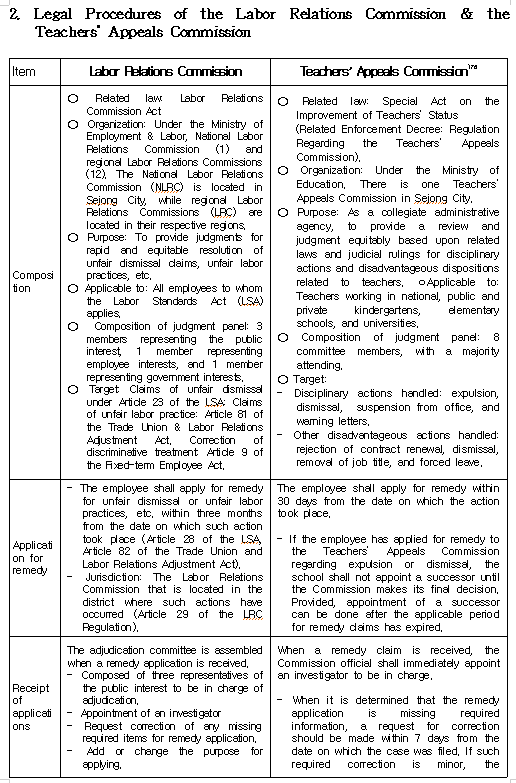

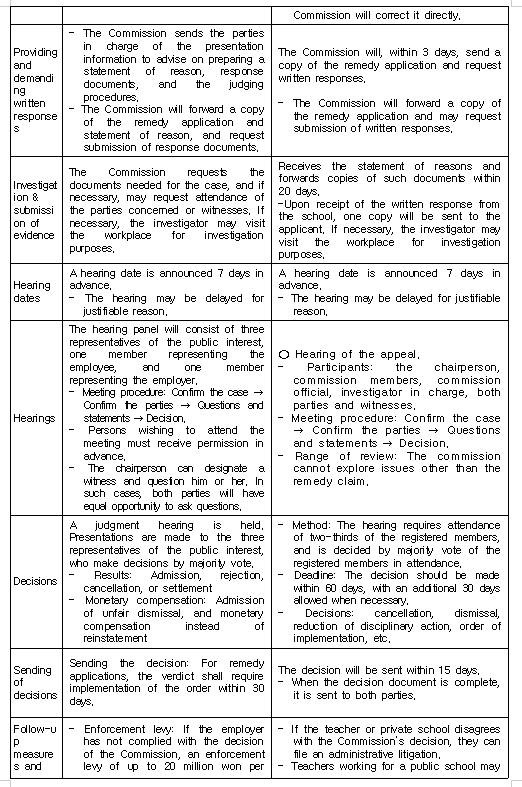

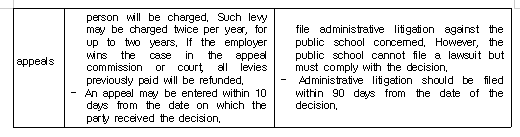

I. Comparison of Functions between the Labor Relations Commission & the Teachers’ Appeals Commission

1. Division of Scope

Individuals subject to applications for remedy with the Labor Relations Commission are employees working for a company that employs five or more employees. Provided, that civil servants working for state or local governments, and teachers, are excluded. Those government servants and teachers to whom Korean labor laws do not apply can submit applications for remedy through the Appeals Commission. The State Administration has an Appeals Commission for public servants and the Teachers’ Appeals Commission for teachers, while local administrations have an Appeals Commission for local public servants. The legislative branch and judicial branch of the national government, the Constitutional Court, and the Central Election Management Commission all have their respective appeals commissions.

Teachers have the right of education, guarantee of status, and guarantee of freedom of speech, while at the same time they often have the duties of educating and conducting research and maintaining their professionalism as teachers, but are banned from political activities. Of particular interest, the system related to the guarantee of status is with the Teachers’ Appeals Commission, which deals with teachers’ disciplinary dispositions (such as expulsions, dismissals, suspensions from office, wage reductions, and written warnings), and disadvantageous dispositions (such as forced leaves, dismissals, and removal from one’s position), and this system can involve a kind of administrative trial. Dongchan Lee, “A Study on the Teachers’ Appeals Commissions”, Hanyang Law Study, 22, February 2008, p. 370.

Specifically, teachers are classified as kindergarten “directors and assistant directors” (Article 20 of the Early Childhood Education Act), teachers at elementary schools, middle schools, high schools, advanced technical high schools, or “principals and vice-principals” at special schools (Article 19 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act), as well as those at universities, colleges, colleges of education, and “presidents, deans, professors, vice-professors, associate professors, assistant professors, or full-time instructors” at open schools (Article 14 of the Higher Education Act). Accordingly, employees engaged in a private school’s administrative work, and fixed-term employees, (Article 32 of the Public Educational Officials Act, Article 54-4) do not fall within the scope of the Teachers’ Appeals Act. Instead, they may apply for remedy with the Labor Relations Commission.

3. Characteristics of the Teachers’ Appeals Commission

The Teachers’ Appeals Commission has many positive characteristics, as the system was designed to fit the needs of teachers as follows: ① The Commission cannot implement the worst of the original dispositions on the applicant (Article 16 of the Teachers’ Appeals Regulation). ② When the applicant receives a disposition of expulsion or dismissal, the school cannot assign a replacement until a decision is made (Article 9 of the Special Law for Teachers’ Status). ③ There is no fee for filing an appeal, and the decision on an appeal can be made much quicker than in civil litigation: within 60 days with a possible additional 30 days (Article 10 of the Special Act on Enhancement of Teachers’ Status). Accordingly, the Teachers’ Appeals Commission is the best system for practical remedies by considering the teachers’ guarantee of status, as in the aforementioned items.

II. Conclusion

The foreign professor recognized that rejection by the Labor Relations Commission was not due to the particulars of his case, but due to the wrong commission being asked to handle the case. He also understood that any appeal to the National Labor Relations Commission would not be valid due to the different legal procedure. In his case, there were two options that he could pursue: file a civil litigation, or look for a new job after acquiring a D-10 (job-seeking) visa. In this instance, I suggested that he look for another job instead of filing a civil litigation due to the fact that it could be almost impossible for a foreigner to pursue such civil action due to the expenses and time required. It was disappointing to realize that this was the result simply because he did not know the proper legal protection procedures. Obviously, employees need to become familiar with their applicable legal protection in order to avoid losing their legal rights.