Chapter3. Case Studies on Dismissal

- 5. Cases of Dismissal and Employee Characteristics

-

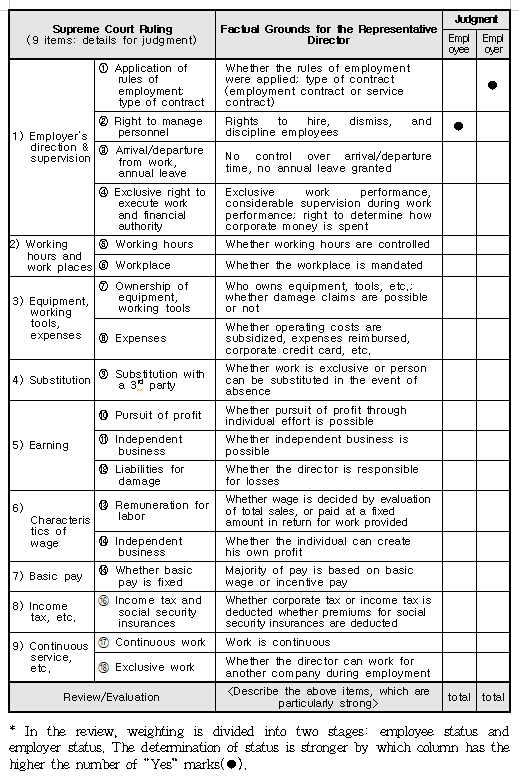

Standard Guide: The Supreme Court ruled, “Whether a person is considered an employee under the Labor Standards Act shall be determined by whether, in actual practice, that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the contract type, such as an employment contract or a service contract. Whether or not a subordinate relationship with the employer exists shall be determined by collectively considering: ① whether the rules of employment or other service regulations apply to a person; whether that person’s duties are decided by the employer, and whether the person has been significantly supervised or directed during his/her work performance by the employer; ② whether his/her working hours and workplaces were designated and restricted by the employer; ③ who owns the equipment, raw materials or working tools; ④ whether the person can be substituted by a third party hired by the person; ⑤ whether the person’s service is directly related to business profit or loss as is the case in one’s own business; ⑥ whether payment is remuneration for work performed or ⑦ whether a basic or fixed wage is determined in advance; ⑧ whether income tax is deducted for withholding purposes; whether the person is registered as an employee by the Social Security Insurance Act or other laws; ⑨ whether work provision is continuous and exclusive to the employer; and the economic and social conditions of both sides. Provided, that as whether basic wage or fixed wage is determined, whether income tax is deducted for withholding, and whether the person is registered for social security insurances could be determined at the employer’s discretion by taking advantage of his/her superior position, the characteristics of employee cannot be denied because of the absence of these mentioned items.” (Supreme Court ruling 2004da29736, on Dec. 7, 2006: Full-time instructors’ employee status.)

[Criteria for Determining “Employee” Status]

Nowadays, there are many kinds of jobs becoming available and people working under service or freelance contracts, but those who are engaged in such jobs are not recognized as employees to whom labor laws apply. In one particular case Supreme Court ruling on June 11, 2015, 2014da88161: CDI unpaid severance pay case.

For these reasons, a clear determination of employee status can resolve labor disputes, and so hereby I would like to review the criteria for determining employee status in terms of legal provisions, expert opinions, and judicial rulings. a large private institute (hagwon) hired instructors under contracts for ‘teaching services’, and treated them as independent business owners with freelancer status, a determination which led to serious labor disputes later on. In cases where an instructor works as an independent business owner and not as an employee, he is ineligible for various protections under labor law such as regulations regarding wages and annual leave, protection from unfair dismissal, and compensation from social security insurances for work-related accidents. However, in cases where an instructor has been determined as an employee, all labor law protections apply. Therefore, instructors look for coverage under labor law, while institute owners seek to avoid employee status for their instructors, due to the additional expenses and the risk of collective action by those instructors.

I. Judgment of Employee Status

1. Concept

Article 2 (1) of the Labor Standards Act stipulates that the term “worker” in this Act refers to a person who offers work to a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the kind(s) of job he/she is engaged in. The concept of “employee” includes the following factors: 1) it is not determined by the kind(s) of job he/she is engaged in; 2) the person works at a business or workplace; 3) the person offers work to earn wages. In understanding this concept, wage is put at the center, while the key point to be considered is whether a subordinate relationship exists between the work provider and the work user. That is, “employee” means “a person who offers work to earn money through a subordinate relationship”. Jongryul Lim, 「Labor Law」, 13th ed., 2015, Parkyoung sa, p. 32.

A subordinate relationship is one where a person hired by the employer provides work to the employer, and under the employer’s direction and orders, carries out the tasks the employer wants done. So, an employee who offers work to earn wages can be translated as “a person offering work under a subordinate relationship with an employer.” Kaprae Ha, 「Labor Law」, 27th ed., 2015, Joongang Economy, p. 102.

The views of “subordinate relationship” by scholars can be classified into two groups: 1) interpretational and 2) law-based.

2. Scholarly views

(1) Interpretational

This view claims that the current judicial ruling regarding the criteria for determination of employee status has some difficulty in understanding because its criteria are enumerated with factual evidence in parallel order. To overcome this problem, the criteria should be categorized into substantial signs and formal signs from which employee status can be determined as existing or not. Sungtae Kang, “Different types of employment, and judgment of employee status under the Labor Standards Act”,『Labor Law Study』No. 11 ho, 2000, p. 35.

Such substantial signs include whether there is command and control, the relationship between the work offered and the current business, and the work provider’s situation. The formal signs refer to items whose existence depends on the employer’s decisions, which include whether income tax and social security insurance premiums are paid, whether personnel evaluations for the person are performed, and whether the person has a contractual duty to receive permission before getting a second job. Sungjae Yoo, 『Legal arrangement according to the variety of employment types: employee status in non-traditional employment』, Korea Legislation Research Institute, 2003.

That is, this view holds that employee status can be determined through the substantial signs, and formal signs can be excluded from the factors that determine a subordinate relationship.

(2) Law-based Jonghee Park, “Employee concept according to the Labor Standards Act”, 『Labor Law Study』, No. 16 ho, 2003, pp. 74-76.

This view holds that the concept of ‘employee’ should be interpreted in accordance with the related legal provisions. Korean labor law has the definition of employee in Article 2(1) of the Labor Standards Act (“the LSA”), and any judgment of employee status should begin with the interpretation of this provision. The LSA definition of ‘employee’ contains four determining factors; ① the status can be determined “regardless of the kind of job”; ② the person offers work “to earn wages”; ③ the person offers work “at a business or workplace”; and ④ “the person offers work”. Of these four factors, “status can be determined regardless of the kind of job” is not directly related to establishing employee status, and so will not be included for consideration.

First, the employee provides work to earn wages. “The term ‘wages’ in the Labor Standards Act means wages, salaries and any other money and valuable goods an employer pays to a worker for his/her work, regardless of how such payments are termed.” (Article 2(5) of the LSA) Therefore, it is sufficient to prove that wages are paid in return for work, but there is no limit on how such payments are termed. Therefore, even though wages were paid per unit of work performance, without considering the unit for the number of working hours, as long as they are paid in return for labor service, such payment can be regarded as wages.

Second, “at a business or workplace” means that the employee provides work on the employer’s business premises or workplace. Even though there are no particular instructions regarding working hours, place, and method of work, the person is assigned to the labor area with tangible work duties.

Third, “the person offers work” means that the employee provides work to the employer, which is known to be a subordinate position. The employer’s instructions can include instructions regarding time, place, and type of work provided. In determining employee status, all three of these factors do not have to be present, but whether the employee was supervised and under the employer’s instructions or not must consider all of them.

3. Judicial ruling

(1) Criteria of the judicial ruling

The Supreme Court gave clear criteria for determination of employee status in a lawsuit involving a full-time instructor at a private institute: first, employee status may exist regardless of the type of contract; second, the criteria for determination of a subordinate relationship are enumerated to 12 items; third, the conditions suggested as signs of employee status shall be determined as decisive or not by considering whether the employer can unilaterally decide whether those conditions exist. These criteria are used to determine employee status, and they are stipulated in the following paragraph. The Supreme Court Supreme Court ruling 2004da29736, on December 7, 2006: Full-time instructors’ employment status

ruled, “Whether a person is considered an employee under the Labor Standards Act shall be determined by whether, in actual practice, that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the contract type such as an employment contract or a service contract. Whether or not a subordinate relationship with the employer exists shall be determined by collectively considering: ① whether the rules of employment or other service regulations apply to a person; ② whether that person’s duties are decided by the employer, and ③ whether the person has been significantly supervised or directed during his/her work performance by the employer; ④ whether his/her working hours and workplaces were designated and restricted by the employer; ⑤ who owns the equipment, raw materials or working tools; ⑥ whether the person can be substituted by a third party hired by the person; ⑦ whether the person’s service is directly related to business profit or loss as is the case in one’s own business; ⑧ whether payment is remuneration for work performed or ⑨ whether a basic or fixed wage is determined in advance; ⑩ whether income tax is deducted for withholding purposes; ⑪ whether work provision is continuous and exclusive to the employer; ⑫ whether the person is registered as an employee by the Social Security Insurance Act or other laws, and the economic and social conditions of both sides. Provided, that as whether basic wage or fixed wage is determined, whether income tax is deducted for withholding, and whether the person is registered for social security insurances could be determined at the employer’s discretion by taking advantage of his/her superior position, the characteristics of employee cannot be denied because of the absence of these mentioned items.”

“The above criteria are not applied formally or uniformly, but in the event facts equivalent to the above items exist, it should be determined after reviewing whether these facts were decided by the employer’s superior position or required naturally by such job characteristics.” Supreme Court ruling on May 11, 2006, 2005da20910: Ready-mix truck driver case.

(2) Understanding the judicial judgment

In reviewing the court’s criteria for determining employee status, three key items need to be explained. First, when determining whether employee status exists, the judicial ruling is decided by the definition provision of Article 2 (Paragraph 1) of the Labor Standards Act. “In determining employee status under the Labor Standards Act, this shall be determined by whether the person has provided work to the employer through a subordinate relationship for the purpose of earning wages at the employer’s business or workplace.” This judicial ruling includes a definition of the term, ‘employee’, which means a person providing work in return for wages through a subordinate relationship with the employer.

Second, the court ruled, “Whether a person is considered an employee under the Labor Standards Act shall be determined by whether, in actual practice, that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the contract type, such as an employment contract or a service contract.” This judicial ruling shows that employee status shall be recognized not based upon the formal type of contract made between two parties, but by the substantial relationship in actual practice.

Third, the judicial ruling shows that status as an employee under the Labor Standards Act shall be determined by whether the person provides work through a subordinate relationship or not, and in order to confirm such subordinate relations, several signs are listed and estimated collectively. In particular, these signs can be divided into 12 items, which can be compared and analyzed for similarity to employee characteristics and for similarity to employer characteristics. After reviewing which characteristics are more evident in the relationship in question, determination of whether employee status exists shall be made.

II. Opinion

The scholarly view and judicial view are consistent in the following criteria: 1) In employment relations, employee status shall be determined by whether there is a subordinate relationship between the parties or not (judgment by subordinate relations); 2) whether there is a subordinate relationship between the parties or not shall not be determined by the type of contract or title, but by actual facts of the labor provision relations (judgment based upon actual relations); and 3) the actual facts of the labor provision relations shall be determined in consideration of an overall collective evaluation of all items (overall consideration). Accordingly, employee status according to subordinate relations shall be determined after considering practical facts of the employment and reviewing them overall. Judicial ruling states that the criteria for ruling on employee status shall not be determined by the format of employment relations, and shall not consider as important in judgment whether the person paid corporate tax or was registered for the social security insurances, which can easily be decided by the employer due to his/her superior position. These points emphasize that employee status shall be determined by employment relations in actuality.

[Freelancers and Employees]

I. Whether or not a Freelancer is Considered an Employee (A Recent Case)

A Freelance Contract (or Service Contract) refers to an agreement where one party (the service recipient) entrusts another party (the service provider) with particular work, and the service provider accepts it (Commission: Article 680 of the Civil Act). Unlike an employment contract where an employee is to provide work under direction and supervision of an employer, a Freelance Contract shows that the service provider (freelancer) has been commissioned to provide a specific service, and will work independently. As a freelancer, an individual contractor independently disposes the work assigned to him or her by the service recipient, receives limited directions and is under no supervision. The service provider, therefore, is excluded from the application (and protection) of labor law.

On February 22, 2011, 17 native English teachers who had worked for Hagwon C, one of the biggest language institutes in the country, filed a petition with Kangnam Labor Office against Hagwon C for unpaid wages of 350 million won in severance pay, etc. Hagwon C claimed that as these teachers were freelancers and had signed an ‘Agreement for Teaching Services’, they were not entitled to severance pay as normally required under Labor Law. However, the 17 teachers claimed that even though their contracts were Freelance Contracts, they had a) provided labor service under Hagwon C’s direction and supervision and even under its strict control, b) their workplace and working hours had been restricted, and c) they had received fixed hourly wages. The major issue in this labor case was whether the teachers were Hagwon C employees to which the Labor Standards Act applied, or whether they were freelancers (service providers under civil law). In the following pages, I would like to concretely clarify the issue, based on related judicial rulings and administrative guidance on whether these 17 teachers of Hagwon C should be considered to have employee status.

II. Labor Cases Denying Employee Status to Freelancers

(1) A substitute driver is not an employee under the Labor Standards Act

“The substitute driver cannot be an employee when considering the following items collectively: The company provided the substitute driver with customer information from someone requesting a substitute driver. The substitute driver purchased a mobile phone privately in order to receive this information and also paid the mobile phone bills himself. In addition, he purchased car insurance privately to deal with possible car accidents while doing such work. The substitute driver was able to come and go to the office freely, and received payment according to work done. He did not receive fixed pay. The company could not punish him for negligence or disobedience because company service regulations did not apply to him.” (Daegu Court 2007 gadan 108286)

(2) If a director performs his work duties independently and at his own discretion without specific directions or supervision over his work performance, such a director is not considered to be an employee.

“The director cannot be an employee when considering the following items collectively: The person was registered as a director in the corporate register. He had carried out his duties independently at his own discretion. He had paid his expenses with the company credit card, used the company car independently, and had not received any directions or supervision of his work performance from the company, but simply reported to the representative director.” (Court 2005 guhap 36158)

(3) Even though the person has provided labor service, if he was not in an employment relationship, he cannot be regarded as an employee under the Labor Standards Act.

“The person cannot be an employee when considering the following items collectively: Even though the employee’s place of work was restricted to company premises and the company could not substitute him with other employees, the service provider was not limited to specific working hours when his coming to and leaving the office was controlled. The company did not have any authority to discipline the person for violation of service regulations, even though the company exercised some rights to direct and supervise in the course of work performance. His earnings were not remuneration for his labor service, and he did not receive fixed or basic pay. The establishment or termination of the labor service contract was up to the service provider.” (Busan District Court Ruling on May 17, 2006, 2005 gudan 1293)

(4) A private tutor who receives a commission due to results for the number of commissioned duties performed is not an employee.

“A private tutor cannot be an employee when considering the following items collectively: The private tutor did not receive substantial or direct orders nor was supervised by the company in the process of performing the required duties. Unlike a regular employee of the company, the private tutor was hired by a branch office, and had not had his/her work hours controlled, was free to have duplicate employment, and could terminate the service contract at any time. Payment was made regardless of the contents of the labor provided, or the time that the private tutor worked. Rather, payment and amount were decided by the results of the commissioned duties performed. It is therefore difficult to deem the payment as remuneration paid in return for work.”(Administrative Court 2003 guhap 21411)

(5) A golf caddie cannot be considered an employee under the Labor Standards Act.

“A caddie cannot be an employee when considering the following items collectively: the caddies in question did not receive any monetary remuneration from the company except for service fees. They were assigned to work in a specific order, but did not have their working hours regulated, and so whenever they finished their work, they could leave the golf course immediately. In the process of work performance, they did not receive any substantial or direct orders or supervision from the company, but simply provided their labor service according to the needs or direction of the golf players.” (Seoul Admin. Court 2001 gu 33013)

III. Concrete Criteria for Determining "Employee" Status

“Whether a person is considered an employee under the LSA shall be decided by whether that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages in actual practice, regardless of whether the type of contract is an employment contract or service agreement under civil law.” (Supreme Court 2008 da 27035)

The Ministry of Labor determines whether the contractor has employee or freelancer status when considering collectively the seven items suggested below by the aforementioned Supreme Court ruling.

(1) Whether the Rules of Employment or service regulations apply to a person whose duties are decided by the employer, and whether the person has been supervised or directed during his/her work performance specifically and individually by the employer: Supervision and direction mean that the person implements the work that the employer wants him/her to do under the employer’s direction and command. There are various criteria for determining “under the direction and supervision of the employer”, but this shall be determined by considering the following criteria collectively.

① Whether such things as employment, training, retirement, etc. apply to said person;

② Whether said person can decide what work he/she will do, or whether said person has freedom to obey or reject work instructions.

(2) Whether his/her working hours, working days and workplaces are designated and restricted by the employer: ① Whether his/her working hours or working days are designated: falls under “Restrictions in working hours”; ② Whether his/her workplaces are designated or the times determined when said person shall provide labor service in the directed workplaces: falls under “Restrictions in workplaces.”

(3) Whether a third party hired by said person can be a substitute for him/her: The inability to substitute someone for oneself to do the labor service is not a basic criterion in determining whether a subordinate relationship exists or not, but when a substitute is possible, this becomes a significant indicator that a relationship of direction and supervision may not exist.

(4) Whether said person owns the equipment, raw material, or working tools he/she uses: If the machine or tools owned by the work performer are very expensive, and if the person shall be responsible for his/her own workplace injuries, he/she is closer to being a business owner who judges and takes on risk at his/her own discretion, and indications that he/she is an employee are weak.

(5) Whether payment is remuneration for work and whether a basic wage or fixed wage is determined in advance:

① If remuneration is a fixed amount regardless of work performance and paid at a fixed rate for work, and if the fixed amount is designed to provide a living for the person, this can be described as characteristics of being an employee;

② If the person’s level of remuneration is remarkably higher than other employees who do the same or a similar job in a corresponding company, this can be remuneration for a business assignment with individual responsibility and risk and not a characteristic of being an employee.

(6) Whether work provision is continuous and exclusive to the employer: If the person is restricted from simultaneous employment with another company by company regulations, or if the person cannot work for two or more companies at the same time due to his/her unavailability in reality, said person’s provision of labor service can be regarded as exclusive to the employer.

(7) Whether the person is registered as an employee under the Social Security Insurance Acts or other laws: In cases where the person pays income tax on his/her remuneration, this is a supplementary fact that can be positively determined as an employee characteristic. However, simply because remuneration has not been subject to income tax is not a clear indication that this remuneration isn’t a wage.

IV. Judgment on Employee Status of Hagwon Teachers (Conclusion)

The English teachers of Hagwon C in the above-mentioned labor case were judged by the Labor Office to be employees providing labor service for the purpose of earning wages. It was confirmed that what they claimed as unpaid wages (such as severance pay, paid weekly allowance, and annual paid leave allowance) were actually unpaid wages guaranteed by the Labor Standards Act. As the decision of the Labor Office has not been made public, I assume that the judgment can be understood through the following labor case.

“Teachers are considered employees who provide labor service under employment relations and are entitled to severance pay.” (Suwon Court 2007 godan 5596)

① The Hagwon determined what subjects teachers would teach, and stipulated teaching hours and workplaces for the teachers.

② The Hagwon repeatedly delivered letters to encourage teachers to improve quality and content of their classes, and sometimes sent out general rules regarding its operations. In reality, teachers had generally been directed and supervised in many ways.

③ The Hagwon owned all furnishings, materials, and equipment that teachers used, with the exception of lesson materials.

④ Teachers could not be substituted by a third party in reality, except for very exceptional cases such as illness or unexpected tragedy.

⑤ Teachers received remuneration calculated by multiplying a fixed hourly amount by the number of working hours. The remuneration was paid in return for work itself, and the Hagwon’s earnings did not affect individual teachers’ level of remuneration.

⑥ On the other hand, some teachers had taught at other hagwons while working for the employer, which may be problematic to being declared “exclusive to the employer”, but in reality, such teachers’ classes at this Hagwon were relatively smaller.

⑦ Even though the Hagwon had two systems of employment for staff and teachers, did not apply the rules of employment to teachers, did not charge income tax, and let teachers insure themselves through the individual National Health Insurance outside of the company’s National Health Insurance, these conditions are secondary in evaluating employee status as the employer can determine these conditions due to his/her superior position in employment relations.

[Dismissal of a Korean Branch Manager(Recommended Resignation)]

As more foreign-invested companies have come into the Korean market, dismissals of Korean branch managers have occurred more frequently. Generally, in cases where the branch manager represents a virtually-independent workplace in Korea, he or she can be regarded as a commissioned employer rather than an employee under an employment contract, and therefore not subject to employee protections under the Labor Standards Act. However, during the beginning stages of investment, there is a high possibility that branch managers of foreign companies may be considered employees in practice, since foreign companies generally start up Korean sales offices or liaison offices at the beginning. Later, the status of “employer” may be accepted for the branch manager as these offices gradually expand their business and become independent in corporate operation, management of personnel, and accounting.

In cases where the branch manager is an employee to whom the Labor Standards Act applies, the employer can only dismiss him or her for ‘justifiable reason’. In cases where he or she feels the dismissal has been unfair, the branch manager may seek legal remedy from the Labor Relations Commission in accordance with the remedy application process, which may include reinstatement, retroactive pay during the period of dismissal, or monetary compensation. Of course, if the branch manager is considered to have employer status, termination of commissioned relations is easier, in accordance with the details of the commission agreement signed by the foreign company head office and the branch manager. However, as the branch manager’s legal status is not always clear, a pragmatic approach which seeks peaceful resolution involving mutual compromise will help to avoid legal risk. One such approach is for a company to recommend resignation.

In this article, I will deal with the characteristics of branch managers in terms of both employee and employer, and then through an actual labor case, I will explore the use of company-recommended resignation as a way of resolving potentially difficult cases.

I. Determination of a Branch Manager’s Employment Status

1. A branch manager’s status according to the Labor Standards Act

The term “employee” in the Labor Standards Act means “a person who offers work to a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the kind of job he/she is engaged in.” Factors necessary to be considered an employee include “regardless of the kind of job”, “in a business or workplace”, and “a person who offers work…to earn wages.” In the definition of “employee”, wages is the central concept Lee Byungtae,『Labor Law』, 9th ed., Chungang Economy Co., p. 55.

, with the secondary factor being whether there is a subordinate relationship with an employer. This means that “employee” refers to a person who provides work in a subordinate relationship to earn wages. Lim Jongryul,『 Labor Law』, 11th ed., Parkyoung Co., p. 29 제11판.

As a Supreme Court ruling Supreme Court ruling on December 7, 2006. 2004da29736.

has stipulated, “Whether it is appropriate to regard a director as an employee defined by the Labor Standards Act has nothing to do with the manner in which the contract is made but whether the director was paid to provide a service that requires him to be subordinate to another. Regardless of whether he/she is holding the position or title of a company director or auditor, in the real sense or just in name, as long as he/she receives remuneration as compensation for providing a specific labor service under the direction and supervision of the employer or he/she receives remuneration as compensation for taking charge of a specific labor service under the direction and supervision of persons such as the representative director in addition to the duties assigned to him/her by the company, such a director can be regarded as an employee as defined by the Labor Standards Act.” This judicial ruling determines that whether a branch manager is an employer or not depends on whether or not he/she has independent operational authority.

In addition, the Supreme Court ruling suggests that the following items shall be considered substantially and collectively when determining whether a person is an employee or not:

(1) Whether the rules of employment or service regulations apply to the person in question, and whether that person has been supervised or directed during his/her work performance specifically and individually by the employer;

(2) Whether his/her working hours and workplaces are designated and restricted by the employer;

(3) Who owns the equipment, raw materials, or working tools; and

(4) Whether payment is remuneration for work, whether the basic wage or fixed wage is determined in advance and whether income tax is deducted for withholding.

2. Criteria for judgment on a branch manager’s status

Judicial rulings related to employee characteristics under the Labor Standards Act offer the following three guidelines:

(1) Employee status shall be decided by whether that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages in actual practice, regardless of the type of contract;

(2) Employee status shall be decided by actual practice regardless of whether the contract is an employment contract, a commissioned contract or service agreement under civil law. That is, employee status shall be determined by the substantial relations implemented in actual practice, not as stated in a formal contract format; and

(3) Employee status under the Labor Standards Act shall be decided by whether that person “provides labor service” in a subordinate relationship. Subordinate relations shall be determined by considering several standard factors collectively.

II. Dismissal of a Branch Manager: A Case Study

1. Summary

A French law firm requested legal advice regarding the dismissal of a Korean branch manager at the Korean branch of a French company in early December 2014. The labor lawyer from this particular French law firm had received the necessary information regarding legal determination of the branch manager’s status, preparation of dismissal proceedings, details on legal risks, as well as practical methods on implementation of the dismissal, and was double-checking them by phone. Several days later, the vice-president of the Asia head office located in Tokyo, Japan, visited and made substantial inquiries about legal relations, the company’s responsibilities according to the employment contract, the dismissal process, required documents for dismissal, and advice on successfully terminating the employment relationship face to face. After making preparations based on this legal information, the vice-president met the branch manager on December 17 and terminated the employment relationship peacefully through a recommended resignation rather than outright dismissal.

2. Basic information on the branch manager

1) Number of employees for whom responsible: 100 (30 at the Seoul head office, 70 at the Busan plant)

2) Position and type of contract: President, employment contract signed in Korea

3) Nationality: Australian Korean law applies to labor disputes occurring in Korea in accordance with the ‘territorial jurisdiction’ principle’. Even though both employer and employee have foreign nationality, Korean labor laws are preferentially applied. The following shows the relevant content and basic reference for governing law.

The Conflict of Laws: Article 28 (Employment Contracts) 1) For employment contracts, regardless of the governing law that both parties agreed, it is not possible to ignore the employee protections endowed by compulsory rules of the resident country related to the governing law stipulated by Paragraph 2. 2) If neither party chose the governing law, the employment contract usually follows the law of the country where the employee provides labor service ordinarily. If the employee does not provide labor service in a particular country, the governing law shall be the law of the country where the business office exists that hired the employee.

4) Contract signing date: April 2, 2012 (Service period: 2 years and 8 months)

5) Basic annual salary: 300 million won plus 20% performance bonus

6) Status: Registered representative director with limited authority to operate company business at the Korean branch, and manage personnel and accounting

7) Articles related to termination in the employment contract: 60 days’ average wage for each service year in terms of severance pay; termination possible with 30 days advance notice in the event poor business performance is determined.

III. Legal Review & Evaluation of the Case, and Use of Recommended Resignation

1. Legal review

In dealing with this case, I provided a legal review of the branch manager’s status to the labor lawyer of French law firm “A” from early December 2014. The process of dismissal in this case was well-implemented and followed the termination procedures suitable to the branch manager’s status and according to relevant documentation. Following are the questions asked by law firm “A” and the responses given by this labor attorney.

Q: What is the best way to breach the employment contract?

A: In reviewing the employment contract and judging the branch manager as having “employer” status, it is possible to dismiss him or terminate the employment contract by recommending resignation in accordance with the contract details where the branch manager can be dismissed due to poor business performance results.

Q: In the event of failure of negotiations for recommended resignation, is there possibility for legal dispute?

A: If the branch manager rejects the recommended resignation and plans to take legal action and claim employee status, the company can terminate his employment with 30 days’ notice according to Article 6. 2 “Termination of the Employment Agreement”. As the branch manager has “employer” status, he cannot apply for remedy. Current labor law protects employees only. However, if the branch manager’s status is judged as an employee, the company may encounter serious problems in this dismissal case.

Q: What are the required documents for the recommended resignation procedure?

A: The company shall prepare two documents: (1) the Settlement Agreement for Voluntary Resignation, and (2) a dismissal notice. The company shall notify the branch manager of its intention to terminate the employment contract due to poor sales results in a final discussion with the branch manager, and recommend that he resign. If the branch manager refuses to resign, the company should deliver to the branch manager the strong message that the company can dismiss him immediately and only pay the dismissal allowance in lieu of 30 days’ notice.

Q: What can be expected as the worst-case scenario if the branch manager refuses to resign?

A: The branch manager is not protected by the Labor Standards Act, and there should be no problem even if he refuses to resign. In civil law, there is a law regarding the responsibility for non-implementation of a contract, but termination due to the branch manager’s poor sales results can be enough for the company to terminate this commissioned relationship justifiably. As termination of the contract can be accepted as justifiable, there would be no possibility for the branch manager to begin proceedings for a civil suit.

However, if the branch manager is judged to be an employee, he could apply for remedy for unfair dismissal with the Labor Relations Commission, or litigate in civil court to nullify the dismissal. The company should be prepared to counter these things, as they can cause significant difficulties for the company in Korea, and cost a lot of money.

Q: How much will handling a recommended resignation cost?

A: Even though the branch manager’s performance was insufficient, he has contributed to the company so far and has maintained a relationship in good faith with other employees of the branch office. Therefore, an amicable termination of the employment contract would be desirable, which of course can be done through a recommended resignation. The basic cost for that would be 4 months’ wages as severance pay for the two years’ service, as well as a termination bonus equivalent to (X) months’ wages. This termination bonus should consider previous precedents, the company’s ability to pay, the branch manager’s service years and his expectations, etc.

2. Evaluation

Although foreign company branch managers work as the head of Korean branch offices in a capacity seemingly identical to employers, they actually work according to instructions from company headquarters and are therefore more like employees to whom Korean labor law applies. If a company intends to dismiss such branch managers, there should be justifiable reasons for dismissal. If the reason cannot be sufficiently explained, a termination settlement would be desirable which includes a termination bonus upon agreement to resign. The above case involving dismissal of a branch manager can serve as a good example where the company involved sought advice from a professional legal advisory service as to the legal risks and then was able to make sufficient preparations to amicably terminate labor relations.

3. Use of the recommended resignation system

Recommended resignations can be the most desirable way to avoid labor disputes between employers and individual employees because employment relations are terminated after mutual agreement. As labor laws in Korea do not allow employers to dismiss employees without justifiable reason, companies use many methods to encourage employees to agree to resign. In cases of employee redundancy, if the relevant employee refuses to agree to resign, it can be quite difficult to resolve the situation in a satisfactory way for both parties.

As recommended resignations with monetary compensation are used only by companies seeking to resolve particular situations, employees who are suddenly pressured to resign generally feel that the compensation offered is not equal to the potentially long-term uncertainty and urgency to get another job. This has usually led to long labor disputes. Accordingly, in order to prepare for cases where an employer wants to terminate employment unilaterally without any of the justifiable reasons required by the Labor Standards Act, companies can prevent labor disputes in the near future by introducing a mutually-agreed monetary compensation package in the rules of employment or the individual employment contract.

[Representative Directors of Foreign Company Subsidiaries]

In general, labor law does not apply to a representative director because he has a delegated contractual relationship with his employer. This means that he is not entitled to retirement benefits, compensation for industrial accidents, unemployment benefits, legal protection from unfair dismissal, or other things that ordinary employees enjoy. A representative director does not have employee status because he is an ultimate decision maker who represents the company externally and has the right to decide personnel, operations and funding. However, if a representative director is employed by an actual employer and registered on the corporate register, even if simply for the sake of formality, as a representative for external activities, and if his work is performed under considerable supervision from the employer, he is recognized as an employee under the Labor Standards Act.

When a multinational corporation establishes a company in Korea, a local person is commonly hired as the representative director for efficiency and effectiveness. In this case, regardless of his legal status as a registered director, the representative director or the head of the company in Korea often does not have the authority of an employer. In this regard, I would like to examine specifically the distinction between employee and employer, some characteristics of foreign company subsidiaries, and the criteria for determining whether a representative director is also an employee.

I. The Distinction between Employee and Employer

1. The concept of employer

The term “employer” means a business owner, or a person responsible for management of a business or a person who works on behalf of a business owner with respect to matters relating to employees (Article 2(1-2) of the Labor Standards Act, or LSA). Here, the term “employer” means a person who operates a business through employees (Article 2 of the Wage Claim Guarantee Act). The person responsible for management of a business means a person who is responsible for general business management and is entrusted with comprehensive delegation authority from the employer for management of all or part of the business and is able to represent or delegate the business externally. This includes representative directors, registered directors and others. Regardless of whether the position includes “representative” or “director” in the name, the person who actually exercises the management rights of the company is the manager. Supreme Court ruling on May 11, 2006, 2005do 8364; Jongryul Lim, 『Labor Law』, 14th ed., 2016, Parkyoungsa, p. 40.

The representative director or director is a person with rights to represent the company, holds executive power according to the company's articles of incorporation, is entrusted with certain administrative powers by the company, and is not an employee under the Labor Standards Act. However, if a representative director is employed by an actual employer and registered on the corporate register, even if simply for the sake of formality, as a representative for external activities, and if his work is performed under considerable supervision from the employer, he may be an employee as stipulated by the Labor Standards Act. Supreme Court ruling on Sep. 26, 2003, 2002da64681.

2. The concept of employee

The term “employee” means a person who offers work to a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the kind of job he/she is engaged in (Article 2 (1-1) of the LSA). Whether or not a person has employee status depends on whether or not that person has provided work to an employer, in a subordinate relationship, that is performed to earn a wage, regardless of the type of contract. Supreme Court ruling on Sep. 26, 2013, 2012do6537.

Because of his authority to represent the company externally and enforce the business of the company internally, a representative director has employer status. However, if the representative director position is only formal or nominal, if his management is considerably under the direction and supervision of the actual employer, and if he is paid wages in return for the work, the person in that representative director position is an employee according to the Labor Standards Act. Supreme Court ruling May 29, 2014, 2012da98720.

II. Characteristics of a Representative Director of a Foreign Company Subsidiary

1. Representative directors of foreign company subsidiaries

If a domestic foreign office established by a multinational corporation manages its business independently with a certain authority and the representative director is delegated with the right to independently manage the local business within a certain scope, that representative director retains employer status.

In this regard, a judicial ruling states that, "Generally, multinational corporations are a group of several corporations of different nationalities, and legally separated. A multinational corporation as a business group is not comparable to a group of constituent companies but to a parent company which is the ruling supervisory head and is at the top of its subsidiaries, collectively deciding all matters concerning the multinational corporation. Subsidiaries are under the control of the parent company, and there is a controlling subsidiary relationship between the parent company and its subsidiaries.

Accordingly, there is a certain supervisory relationship between the parent company’s executives and the subsidiary company’s executives due to the business connections between the parent and subsidiary. This is similar to the subordinate relationship between an employer and company employees, but differs in that it is a subordinate relationship that occurs only in the interindustry relationship between a parent and a subsidiary. As a result, as there is a certain directive and supervisory relationship between executives of a controlling parent company and executives of a subsidiary company, directors with executive powers in the subsidiary cannot be regarded as employees of the subsidiary.” Seoul High Court ruling on Dec. 21, 2012, 2012na52795.

Nevertheless, if the representative director of a subsidiary of a foreign company receives directions and is supervised by the parent country during the carrying out of his duties, and is essentially an intermediate manager with almost no independence, he is not an employer but an employee.

2. Determining employee status of a representative director

Whether or not the person is an "employee under the Labor Standards Act" shall be determined by whether he has provided work to the employer in a business or workplace for the purpose of earning wage, Supreme Court ruling on Feb. 24, 1999, 98doo2201; Supreme Court ruling on Feb 9, 2001, 2000da57498.

and not on whether the representative director is registered as such on the corporate register. Supreme Court ruling on Sep. 4, 2002, 2002da4429.

In actuality, a representative director is not an employee because he represents the company externally and has the authority to execute the affairs of the company internally. However, if he is registered as a representative director of the corporation, but does not have the right to execute the internal affairs of the company or handle its external affairs, his title is simply formal and nominal while there is another manager who actually makes the decisions, and if he is provided wages not for his performance in management or work, but according to the nature of the work itself, he is an employee in actuality. Supreme Court ruling on Aug. 20, 2009, 2009doo1440.

Therefore, the two most important factors affecting the determination of whether a representative director of a foreign company subsidiary is an employee or not are: (i) the existence of significant supervision over the representative director, and (ii) whether the person has been registered as the representative director on the corporate register.

(1) Existence of significant supervision over the representative director

"In the course of job performance, whether the employee has been supervised and controlled by the employer substantially and individually or not" was quoted in a lawsuit in 1996 regarding a part-time instructor’s employee status at a private institute. Supreme Court ruling on Jul. 30, 1996, 96do732.

However, in a lawsuit in 2006 regarding the employee status of a full-time instructor Supreme Court ruling on Dec. 7, 2006, 2004da29736.

, the above supervision was reduced to “considerably supervised and controlled by the employer”. For a representative director, whether he is an employee or not depends on whether his work has been considerably supervised and controlled by the employer. This change is due to the diversification of occupations, from the simple structure of production and office employees to the complex service industry. Donghee Bae, “A Study on Employee Status Based on Review of Court Rulings”, Korea University Ph.D thesis, 2016, p. 59; Bongsoo Jung, “A Study on the Employee Status of Native English Teachers”, Korea University MA thesis, 2013, p. 32.

(2) Whether the person has been registered as the representative director on the corporate register

An executive director’s status as employee is often recognized by whether he was registered as a director on the corporate register. In general, registered directors are denied employee status, but this is not the case if his duties are performed under considerable supervision and control. On the other hand, an unregistered director is recognized as an employee in principle, but denied employee status if his own decision-making authority or exclusive right to execute the work is clear. Taesik Ahn, “A Criteria for Determining Employee Status for Registered Directors”, 「Law and Policy」, Vol. 22, Korea Policy Association, June 2014, p. 624.

III. Criteria for Judicial Ruling and Application

1. Criteria for Determining Employee Status

The Supreme Court issued clear criteria for determining employee status in a lawsuit involving a full-time instructor at a private institute in 2006. These criteria can also be used to determine employee status for the representative director of a foreign company: first, employee status may exist regardless of the type of contract; second, the criteria for determination of a subordinate relationship are enumerated as the 9 items in the paragraph below; third, the existence of conditions suggested as signs of employee status shall be determined by considering whether the employer can unilaterally decide whether these conditions exist.

In this case, the Supreme Court Supreme Court ruling 2004da29736, on Dec. 7, 2006: Full-time instructors’ employee status.

ruled, “Whether a person is considered an employee under the Labor Standards Act shall be determined by whether, in actual practice, that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages, regardless of the contract type, such as an employment contract or a service contract. Whether or not a subordinate relationship with the employer exists shall be determined by collectively considering: ① whether the rules of employment or other service regulations apply to a person; whether that person’s duties are decided by the employer, and whether the person has been significantly supervised or directed during his/her work performance by the employer; ② whether his/her working hours and workplaces were designated and restricted by the employer; ③ who owns the equipment, raw materials or working tools; ④ whether the person can be substituted by a third party hired by the person; ⑤ whether the person’s service is directly related to business profit or loss as is the case in one’s own business; ⑥ whether payment is remuneration for work performed or ⑦ whether a basic or fixed wage is determined in advance; ⑧ whether income tax is deducted for withholding purposes; whether the person is registered as an employee by the Social Security Insurance Act or other laws; ⑨ whether work provision is continuous and exclusive to the employer; and the economic and social conditions of both sides. Provided, that as whether basic wage or fixed wage is determined, whether income tax is deducted for withholding, and whether the person is registered for social security insurances could be determined at the employer’s discretion by taking advantage of his/her superior position, the characteristics of employee cannot be denied because of the absence of these mentioned items.” Supreme Court ruling on Dec. 7, 2006, 2004da29736.

“The above criteria are not applied formally or uniformly, but in the event facts equivalent to the above items exist, employment status should be determined after reviewing whether these facts were decided by the employer’s superior position or required naturally by such job characteristics.” Supreme Court ruling on May 11, 2006, 2005da20910: Ready-mix truck driver case.

2. Determining Employee Status Bongsoo Jung, “A Study on the Employee Status of Native English Teachers”, p. 79: adjusted to evaluate a representative director’s employee status.

V. Conclusion

In judging the employment status of a representative director of a foreign company subsidiary, there is a tendency to simply decide by considering whether he has been registered as a director, whether the executive has written a commission contract, and whether he has been given the title of “representative director”. It is common for multinational corporations to have a controlling and dominant relationship with their foreign subsidiaries, which means the directors of those subsidiaries in Korea must report business details to their parent companies and receive instructions in turn. It can be difficult to distinguish between normal corporate relations and whether a director is an employee or not.

The representative director of a foreign company subsidiary is generally comprehensively instructed and supervised by the head office of the multinational company on company operations and does not have the right to manage personnel, has limited executive authority and limited decision-making powers on the use of funds. Even department managers should report their business practices to the department directors at the parent company. In such cases, the representative director of a foreign company subsidiary may be judged to be an employee. Therefore, when judging the employment status of a representative director of a foreign company subsidiary, it is necessary to look comprehensively at the director’s exclusive rights to execute work, the right to manage personnel, and the right to spend company money at his own discretion, not by whether he has formally been registered as a representative director, his Korean title, or has signed a service contract.

[Is a Telemarketer an Employee]

“Specially hired service providers” refer to those who provide labor service on a regular basis in a specific workplace, but who are not yet recognized as employees. Typical jobs include golf-club caddies, home-study teachers, cement truck drivers, and telemarketers. They are not generally recognized as employees because they are not in a subordinate relationship with the employer due to their job characteristics, and also do not provide exclusive services to the employer. However, in recent judicial rulings, if a person is exclusively attached to one workplace, and if there is a considerable subordinate relationship with the employer, such a person can be considered an employee. Previous judgment criteria depended on whether the base pay was given, whether the four social security insurances were subscribed to, and whether income tax was paid, but these things can be determined arbitrarily by the employer, given his or her economically superior position, and so determining whether someone is an employee must now be through determining whether an actual subordinate relationship to the employer has existed or not.

Whether a telemarketer who is a “specially-hired service provider” is an employee or not is decided by how much of a subordinate relationship exists between the employer and the at-home telemarketer at the place of work. Telemarketers are usually engaged in business such as selling insurance, selling targeted real estate, distance sales, etc. Unlike a person working at a call-center, his/her main earnings are determined by individual sales performance, so it is not entirely accurate to call such a person an employee. I would like to look into the employee characteristics of an at-home telemarketer and some typical related labor cases.

I. Criteria for Determining “Employee” Status

1. The Ministry of Labor guidelines and judicial rulings use the same criteria for determining “employee status” for a telemarketer. That is, whether or not someone is an employee shall be estimated by whether a subordinate relationship with the employer exists for the person providing the labor service. Some difference is that the administrative guidelines are inclined to consider related factors (refer to the 9 categories of judicial rulings) with equal weight, while the judicial rulings tend to focus on the actual subordinate relationship in work details rather than related factors, in light of the employer’s economically superior status.

2. Judicial rulings on the criteria to determine employee status is based on the following judgment principle. Supreme Court ruling on Sep 7, 2007, 2006 do 777

“Whether a person is considered an employee under the Labor Standards Act shall be decided by whether that person offers work to the employer as a subordinate of the employer in a business or workplace to earn wages in actual practice, regardless of whether the type of contract is an employment contract or service agreement under civil law. Whether a subordinate relationship with the employer exists or not shall be determined by collectively considering: 1) whether the rules of employment or service regulations apply to a person whose duties are decided by the employer, and whether the person has been supervised or directed during his/her work performance specifically and individually by the employer; 2) whether his/her working hours and workplaces were designated and restricted by the employer; 3) who owns the equipment, raw material, or working tools; 4) whether the person can hire a third party to replace him/her and operate his/her own business independently, 5) whether the person is willing to take the opportunity and risk to earn money or lose it; 6) whether payment is remuneration for work and 7) whether basic wage or fixed wage is determined in advance; 8) whether the person pays income tax or not (including subscription to the four social security insurances) and 9) whether work provision is continuous and exclusive to the employer. However, whether basic wage or fixed wage is determined in advance, whether income tax is withheld, and whether the person is recognized as an employee eligible for social security insurance are factors that could be determined arbitrarily by the employer’s superior economic status. Therefore, just because those mentioned factors were rejected, it is hard to deny that employee characteristics exist.”

II. A Case Where “Employee Status” was Determined to Exist (Dismissal of a Distance Sale Telemarketer) Seoul Administrative Court ruling on Mar 21, 2008, 2007guhap19539

1. Summary

(1) A social welfare corporation (hereinafter referred to as “the company”) employed 30 people and used them as telemarketers for distance sale operations. Since November 11, 2003, the applicant had worked as a telemarketer. The company had proposed a new ‘commission agreement’ to the applicant, and when she refused to sign, the company terminated her employment on October 19, 2006. The applicant then applied for remedy from the Labor Commission, but it was rejected after she was determined not to be an employee, and therefore ineligible. Her appeal with the National Labor Commission was also rejected. The applicant then appealed to the Administrative Court.

2. Job Description

(1) The telemarketers the applicant worked with had sold, over the phone, a monthly magazine published by the company.

(2) The applicant worked from 10 am to 5 pm during the workweek at a partitioned booth in the company’s telemarketing room, and received 22% of each total sale as commission, in addition to an “attendance allowance” of 10,000 won per day, plus 100,000 won per month if they were never absent during each month. This was in lieu of a monthly wage.

(3) The company provided a desk, telephone, and other office items necessary to do business, supervised the telemarketers and decided in advance the contents of the letters to be sent to sponsors.

(4) The company proposed a minimum requirement of 1000 phone calls per month and urged telemarketers to reach that goal, but did not discipline those who did not.

(5) The company had all telemarketers report in writing the details of their consultations with potential subscribers and their contact information before leaving the office every day.

(6) The company gave the telemarketers new instructions and other necessary information at regular monthly meetings, as well as irregular meetings presided over by the operational manager.

(7) The company kept attendance records, and treated two instances of leaving the office early as one day’s absence.

3. Administrative Court Judgment

(1) The company stipulated most of the working methods by providing personal information regarding potential subscribers, defining working methods, and supervising and controlling the content of the letters, but did not make concrete calling targets or dictate the content of the calls.

(2) The working conditions defined in the rules of employment did not apply to the applicant, but application of the company’s rules of employment can be determined arbitrarily and entirely at the employer’s discretion, from a position of superior status.

(3) The company informed the applicant of work-related directions and information and provided training on working methods through frequent meetings, and received concrete work performance results from the applicant.

(4) The company determined the applicant’s working hours and workplace, and monitored total working hours by keeping attendance and giving allowances for that attendance.

(5) The company provided the applicant basic office items necessary for work, including payment of the telephone bills.

(6) As the company always paid 400,000 won in attendance allowances every month, this reflects the characteristics of a basic salary.

(7) The applicant did not pay personal income tax, but did pay corporate tax, and was not subscribed to the social security insurances, something unilaterally determined by the company from its superior status.

(8) As the employee had worked for three years as a telemarketer for the company, this provision of work by the applicant can be considered as provision of continuous and exclusive labor service for the company.

(9) Accordingly, the applicant falls under the status of “employee” according to the Labor Standards Act, and termination of this employment shall be considered a unilateral cancellation of employment by the employer.

III. Cases Where “Employee” Status was Determined to Not Exist

1. Telemarketer Selling Insurance Administrative Guideline: Nojo 68107-874, Aug 2, 2001

(1) Job description

① The telemarketer’s job was to call and sell the company’s insurance products to customers, and received training from the company manager on the products, selling techniques, and other matters necessary to sell successfully.

② The company’s rules of employment did not apply to the telemarketer, but the company’s service regulations related to sales had to be followed.

③ In the mornings, the telemarketer went to the office provided by the company, and every day carried out the assigned work according to the hours scheduled by the company, leaving the office after completing the assigned working hours in the afternoon.

④ There was no restriction on the telemarketer getting another job, but it was in reality impossible to carry out other business.

⑤ For the purposes of work, the telemarketer received a workspace, desk, computer, telephone, etc.

⑥ The company paid an activity allowance characteristic of a basic salary, and an incentive bonus in accordance with individual sales performance.

⑦ The telemarketer just paid corporate tax due to being considered self-employed, and so did not pay income tax or premiums for the four social security insurances.

(2) Judgment of the Ministry of Labor

The matters considered not to be characteristics of an employee were:

① The contract that the company made with the telemarketer was not an employment contract, but a “commission contract” under Article 689 of the Civil Act.

② Even though the telemarketer used the communication equipment provided by the company in carrying out commissioned work for insurance sales, the telemarketer sold insurance simply at his own discretion and according to his capabilities.

③ There was no allowance without generation of business, and even the activity allowance (600,000 won per month) claimed as a basic salary by the telemarketer was only paid in cases where the telemarketer sold at least 10 insurance contracts per month. All insurances and incentive bonuses were paid according to individual performance.

④ Company regulations such as the rules of employment were not applicable, and no disciplinary action (such as reducing allowances) was taken for arriving late, leaving early, or being absent.

⑤ The telemarketer does not have to call the list of customers provided by the company, and no disciplinary action is taken if they are not called. In consideration of the above-mentioned items, this insurance sales telemarketer cannot be considered an employee.

2. Targeted Real Estate Telemarketer Administrative Guideline: Application-6107, Dec 12, 2006

(1) Job description

① The job is to sell real estate for the company to random people over the phone or after consultation at the designated workplace.

② The monthly fixed income that the telemarketer received from the company was 800,000 to 1.2 million won, with 50,000 won deducted for each day of absence.

③ The telemarketer was responsible for consulting with potential customers, carrying out on-site surveys, and concluding contracts. A commission of 8 to 10% of the sale was given.

④ The telemarketer worked five days per week and 8 hours per day at a specified location.

(2) Judgment of the Ministry of Labor

The telemarketer for the targeted real estate company sold land over the phone or through consultations.

① Even though the workplace and working hours were stipulated, this was designed to promote effective sales in accordance with different requirements of telemarketing.

② The telemarketer dealt with people at his own discretion, from attracting potential buyers to completing the contract, and did not receive any concrete or individual supervision or control by the company.

③ What the telemarketer received as a fixed allowance is a kind of sales activity allowance. ④ Income tax was reported.

⑤ The main income was the very high commission received in return for selling the real estate. It is therefore estimated that the telemarketer cannot be regarded as an employee providing labor service under an employer’s supervision and direction.

IV. Opinion

According to the changing business structures, companies use telemarketers for various fields. In the beginning, telemarketers were handled as outsourced or commissioned labor, and no real problems existed. However, companies have gradually been using telemarketers to directly increase operational profit. In this process the company comes to supervise the telemarketer directly, which affects the telemarketer’s status as a commissioned service provider under the Civil Act to that more like an employee to which the labor laws apply. As the telemarketer’s status changes this way, employers need to handle dismissals carefully, deal with severance pay, annual leave, social security insurances, and other protections granted by Korean labor law. Accordingly, employers need to recognize that telemarketers’ status can change from commissioned service provider (under civil law) to an employee (under labor law) according to the degree of employer involvement in the telemarketer’s work. When using telemarketers, it is necessary to consider in advance whether the telemarketer shall be considered self-employed or an employee exclusively supervised and directed.

[Dismissal of a Foreign Pastor]

A foreign pastor (hereinafter refer to as “the Employee”) started to work for an international school (hereinafter refer to as “the Employer”) under contract as a pastor, but was dismissed 6 days after his employment began. The Employee applied to the Labor Relations Commission on April 27, 2009 for remedy, alleging that his dismissal on March 6, 2009 was unfair.

The job description in the employment contract was “Position: Pastor of Church, English Worship. Duties shall include, but are not limited to: preaching, teaching and the provision of overall pastoral leadership.” However, when the Employee first arrived at the school, the Employer assigned 12 hours of Bible/English classes per week to him, contrary to the employment contract. The Employee refused to teach these classes because, according to his contract, his major duties were to preach and fulfill other pastoral obligations, not teach regular classes. The Employer then demanded that the Employee sign a written pledge stating that the Employee would comply with the rules of employment as a teacher, but the Employee refused because he was hired primarily as a pastor, not a teacher, so a written pledge for teachers was not appropriate to his position as a pastor.

The Employer dismissed the Employee because he refused to teach the Bible/English classes, and also refused to sign the written pledge. The central argument in this dismissal case was whether the assigned Bible/English classes were mandatory according to the employment contract or not. The Labor Commission’s decision would be based on whether the Employee’s rejection of the Bible classes was appropriate or not.

I. The School’s Claim

1. As stipulated in the employment contract, the Employee’s job was not limited to any particular duty. The Employee’s view that, as a pastor, he could not perform other duties except his pastoral duties, is contrary to his employment contract. The “teaching” that the Employee rejected was clearly within the Employee’s job boundaries in the employment contract. Even though the details were not specifically included, the Employee had to agree to the employer’s work instructions because of the phrase, “but not limited to...” in the employment contract. In particular, those filling the pastoral position at the Christian School should not only preach to the students, but also provide English Bible classes so that he can share biblical knowledge, fundamental work for a pastor.

2. Signing of the written pledge was requested to ensure a reliable relationship between the employing school and the Employee. This is a general document required by most companies at the beginning of employment. Despite this, the Employee refused to sign the pledge, alleging that the school demanded, in a threatening manner, that the document be signed. Article 10 of the school’s rules of employment (regarding cancellation of employment) stipulates that the Employer can cancel employment for those who do not submit a written pledge. The Employee refused the Employer’s justifiable demand to submit the necessary document, so the Employer took the necessary next step, cancellation of employment, and stated that there was no threatening.

II. The Employee’s Claim

1. When the Employee enrolled his daughter at an international school, he came to know the Employer. At the Employer’s suggestion, the Employee started working part-time for the Employer in February 2008, teaching a Bible class on Friday afternoons and preaching English sermons. Later, the Employer suggested that the Employee work as a full-time pastor at the English church of the school after he finished his contract as a full-time lecturer at a Christian university in Cheonan at the end of February 2009. The Employer and the Employee negotiated over the employment contract for several months, and although the university had offered to renew his contract with a salary increase, the Employee signed a three-year employment contract with the international school, for a monthly salary of 2.7 million won.

2. As already discussed, the Employee, who has a Doctor of Ministry degree, entered into an employment contract as a full-time pastor, at the suggestion of the Employer. If the Employee had known that he would not be a full-time pastor, but a full-time instructor engaged in regular Bible/English classes, he would never have entered into this employment contract with the Employer. After hiring the Employee, the Employer changed the position from being a pastor to a full-time regular instructor, contrary to the contents of the employment contract. When the Employee rejected this change, the Employer dismissed him immediately, within one week after being hired, without any attempt to understand or persuade him to change his mind.

III. Related Judicial Rulings

1. In cases where there is disagreement between the parties in interpreting the contract, logic and experience need to be used when considering the related sections, the motives behind the contract with the disputed article, the purpose desired by the contract, both parties’ real intentions, etc. If the real intentions of either party cannot be interpreted from their expressed intentions, the expected results from externally expressed behaviors (the contents of a written contract) shall be used to indicate real intentions. So, internal opinions of either party are not accurate indicators of real intent. (Supreme Court Ruling Jun 24, 1007, 97da5428)

2. In cases where, according to an employer’s rules of employment, newly-hired employees have a probationary period, whether or not this applies to a specific employee shall be stipulated in the employment contract. If there is no provision in the employment contract that a new employee will have a probationary period, he/she shall be regarded as a regular employee, rather than a probationary employee. (Supreme Court Nov 12, 1999, 99da30473)

IV. Conclusion (Judgment of the Labor Relations Commission)

The major issue in this dispute was to decide whether termination of the employment contract was justifiable, after interpreting the purpose of the employment contract concerned. We came to the conclusion that follows, after considering the claims of both parties, the stated contents of evidence documents submitted, investigations made by the labor commission, facts revealed by answers to our questions, etc.

1. Concerning the purpose of the employment contract